Another great Brexit debate at the ISITC Europe annual bash the other day. I was on a panel with Kay Swinburne, MEP Member of Economic and Monetary Affairs; Rebecca Healy, Lead Analyst of Financial Market Structure at Liquidnet; and Michael Cooper, CTO Radianz, BT Global Banking and Financial Markets at BT; and we had a lengthy discussion about equivalence, passporting and related matters.

Passporting is particularly important for London and the financial markets, as it allows firms to register once for a bank or other financial licence to trade across all EU countries. According to The Financial Times, 5,500 UK-registered companies rely on “passports” to do business in other European countries, and 8,000 EU/EEA financial services companies rely on single-market passports to do business in Britain.

The total number of passports held by UK companies amounted to 336,421 because many have passports for different sectors in different countries, the FCA said. The total number of passports held by European businesses for access to the UK is 23,532. The passports cover a range of activities, including investment banking, corporate lending, insurance, payments and asset management.

Kay was adamant that equivalence would not work, retail markets would lose all passporting rights, and that the UK would not be able to access EU citizens’ data. This would severely restrict London-based FinTechs that want to offer EU services, but all they need to do is register for a bank licence in a light subsidiary in, say, Estonia, and then they can still passport and access data regardless.

What intrigued me is that if passporting AND equivalence are untenable according to Kay, what is tenable? Probably something that Michel Barnier will invent, as he is responsible for the Brexit negotiations from the EU perspective. Bearing in mind that he spent four years at the helm of the European financial markets from 2010-2014, he does have some background knowledge of the City and its role in Europe.

In fact, he has a chart that he used to track and trace the regulatory changes required to bring Europe back from its near financial death during that period, and no doubt will see that London’s role is still key in the investment world. In the retail world, maybe not. If you’re interested in what Barnier actually did whilst in office, this House of Lords report is invaluable: The post-crisis EU financial regulatory framework: do the pieces fit?

Meanwhile, one big area of exposure is our services business. 80% of the UK economy is services-based, and the Brexit issue is that most rules focus on the movement of goods – products – rather than services. We have to get an understanding of services, including financial services, as part of a new trade agreement and the fact that services is so crucial to the UK economy is a big question.

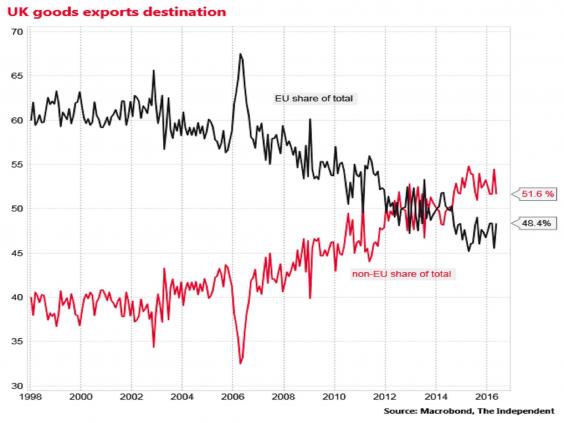

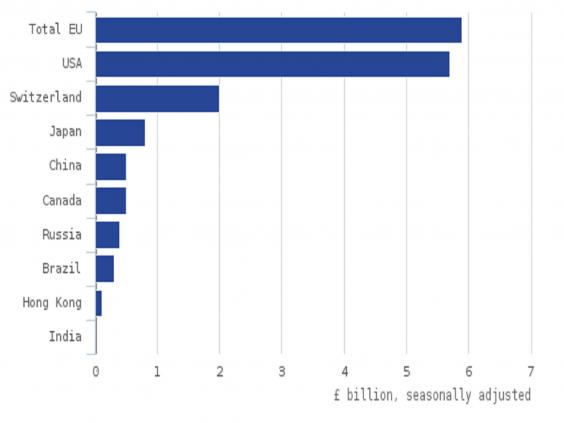

Mind you, as some of the media has pointed out, the UK’s export surplus in the key services sector, which makes up 80% of the economy, has rocketed by 67% with non-EU countries in the last five years. Europe matters, but the UK has for some years been moving outside Europe, as illustrated by these two charts:

The debate finished with an audience question and vote.

The question was: do you believe the City post-Brexit will:

1) Be seriously impacted and lose a significant amount of business (33%)

2) Be better off (2%)

3) Continue as usual (7%)

4) Adapt and create new opportunities (58%)

As you can see, most of the audience – who are investment markets IT professionals mainly – think we will adapt and thrive whilst a third think Brexit will be bad for business.

My own take was that nothing is certain right now. No EU member state has ever left the EU before, so there is nothing right now that shows the future path. The future path has to be negotiated and agreed, and it will be. If in that negotiation we get equivalence or passporting, then that’s great. If we don’t, there will be some practical alternative implemented.

In particular, Brexit is a political change, and the future is determined not just by politicians but by economic, social and technological change. Similarly, politicians are unreliable. What they say today may well not hold true tomorrow. Michel Barnier may say today that the UK gets no special deal for financial services but if, practically, that has to change tomorrow, then it will.

After all, in my experience of EU Directives, when things that will cost billions erroneously and damage trade across Europe, the politicians change their minds. If the stubborn position to remove any access to Europe for London-based financial firms, many of which are American and Asian, is forced through, it would change dynamics fundamentally.

London would still be a global financial hub, but Europe’s access to trade and capital would be seriously impacted by such a move. As a result, EU corporations would lose billions in funding whilst London-based institutions would lose billions in a forced restructuring that would not make sense. As was discussed, when politicians in EU member states find their biggest businesses telling them that what they are doing is harming their business and therefore their economies, they are highly likely to U-turn. We shall see.

From the Financial Times: Financial future after Brexit: passporting v equivalence by Jonathan Ford

The City of London’s main lobby group this week signalled a retreat from fighting to retain the EU financial “passport”, one of two models that would allow companies to continue to sell their services throughout the bloc. The other option is regulatory “equivalence” but what are the pros and cons of each?

Passporting

The EU passport is a legal mechanism that permits financial services companies based and regulated in one country of the EU (or the broader European Economic Area), and authorised under one of the EU’s single market directives, to do business in other member states purely on the basis of their home state authorisation.

Introduced in 1995, it has been expanded and deepened by a series of directives. Since the financial crisis, the EU has set up regulatory bodies to cover banking and securities markets. These have powers to make and interpret rules that are binding on national regulators.

There are two options available to the UK if it wants to retain passporting after Brexit.

First, it could remain within the single market, presumably by joining the EEA, which includes EU countries and also Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway. But that seems unlikely: EEA members must accept free movement and rulings from the European Court of Justice and Theresa May is against both. It would also turn Britain into a passive “rule taker”, because it would no longer have representation on the EU’s regulatory bodies.

The second option is that London based businesses could individually establish subsidiaries within the EU that would have passport rights. The problem for the banks is that this would be inefficient, both increasing regulatory complexity and requiring them to put additional capital — and liquidity — behind the business.

Equivalence

Equivalence is a legal concept that has emerged over the past 30 years to facilitate cross border trading between markets that choose to recognise one another’s standards. Among the first such deals was a 1990s arrangement between the UK and US covering mutual access to derivatives markets.

Some but not all EU financial legislation accepts the principle of equivalence. There is, for instance, no such provision for commercial banking or primary insurance. Some argue these gaps would need to be filled for the mechanism to be a credible option for the UK.

Equivalence does offer certain advantages, in that it does not require both sides to mirror each other’s rules and legislation. Businesses from one jurisdiction can offer financial services in another on the grounds that their standards are similar enough that customers will be protected. So the UK could in theory retain access to the EU market, without having to accept EU jurisdiction or copy out its laws.

Equivalence is not without problems. One is that a declaration of equivalence can easily be revoked — at just 30 days’ notice under existing EU legislation. Banks say this does not make for a sound foundation for long-term investment plans.

Another is the absence of an agreed definition of equivalence. This leaves open the possibility of the EU forcing the UK to implement rules it does not like, in order to remain equivalent. As the Bank of England governor Mark Carney observed on Wednesday, this could result in a loss of regulatory control and even pose a threat to financial stability.

For equivalence to work, most think the UK would need a detailed agreement. This could provide certainty and set out how disputes about definitions and clashing rules could be resolved. Much will depend on the EU’s willingness to risk cutting the City loose, and conversely its desire to retain influence over future UK regulatory developments.

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...