I’ve been asked the same question twice this week in two separate conferences (one in Vienna, the other in San Francisco): “how will we deal with the corruptive forces when we are all on the net?”

The second questioner clarified what she meant by referencing the film Enemy of the State, where Will Smith gets wiped off the network due to being involved in activities the US Government felt were undesirable (this has since been a TV series).

So here’s the plotline that I gave and the concern that the audience feel.

In the future of the Internet of Things, we will have many machines working for us on our behalf. Robots will be serving our food and making our meals; our fridge will replenish itself on an ongoing basis from Wal*Mart or Tesco or whomever; our entertainment centre will manage and order shows based upon our viewing preferences; our car will order its own fuel and replacement parts and servicing; our clothes will recognise when they are worn too much and re-order replacements; and so on and so forth.

In the Internet of Things, we will probably have tens or even hundreds of items with chips inside.

The question is: how do they know they are mine? Who gave my shoes the authority to replace themselves? Who allowed my TV to pre-order the new season of Game of Thrones? And what happens if my car orders a 20,000 mile service for $1,000 without telling me?

These are all good questions, and when you multiply this by seven billion people on Earth all with their internet of things, you are talking 100 billion or more devices communicating, trading and relating through the network with no human hand involved. How can the network work out the 100 devices that belong to me versus the 100 that belong to you?

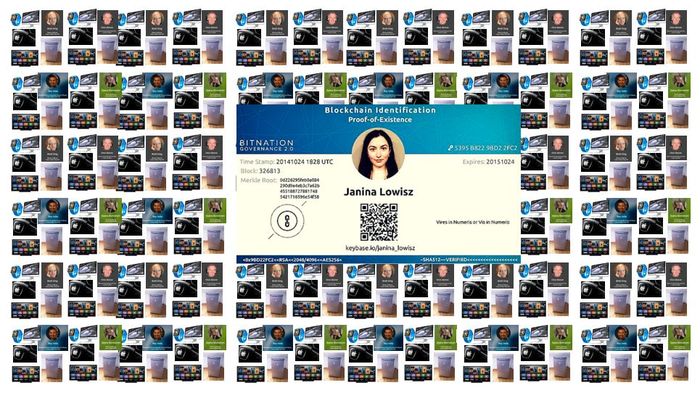

Via a digital identity of course, and that digital identity will sit on a shared ledger sidechain with “Chris Skinner” as the master identifier and “Chris Skinner’s Watch”, “Chris Skinner’s Car”, “Chris Skinner’s Refrigerator”, etc, as sub-identifiers. The fact that the things I own are all tagged with my header information, means that they can trade.

I’ve allowed them to trade with different status levels, so that I have to personally authorise transactions above $50 from my entertainment system, $250 from my refrigerator and $1,000 from my car. In other words, my things are tailored to me.

This net-based personal machine management system is set up once. All new devices are purely added or swapped in and out, and the system works seamlessly for and around me.

But what happens if someone deletes my records? What happens if a cybergang compromise my Digital ID? What happens if the government decides I am engaged in undesirable activity and decide to switch me off?

This is a valid fear, but is it a real one? I could be deleted today if I did undesirable things. It’s called jail, deportation or black-listing. Cybergangs can already compromise my ID by stealing it. I could be deleted from the bank tonight and no-one would know or care except me. So these fears are probably more a representation of fears that pre-existed tomorrow’s digital network rather than being a result of them. There will always be corruption in the system. Our job is to just avoid it or stamp it out.

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...