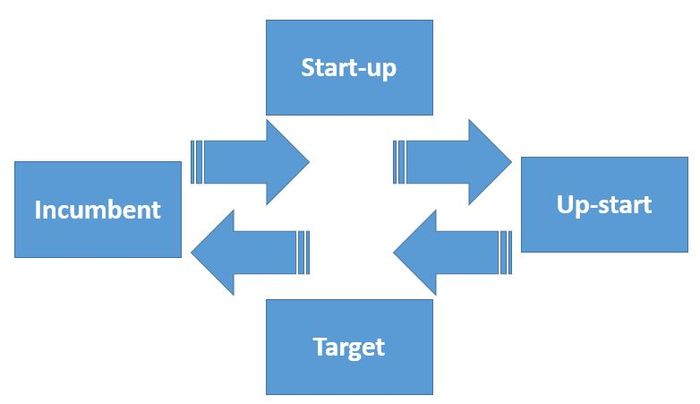

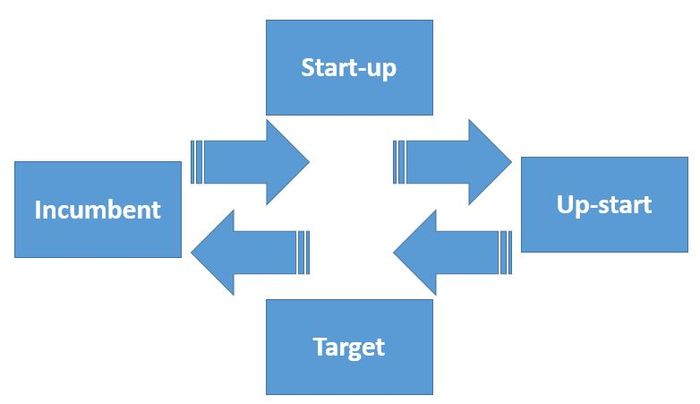

During the third phase of the innovation cycle discussed on Friday, the upstart has been noticed by the incumbents and becomes a target to be attacked.

We saw this with Uber from the taxi firms; with Airbnb, it’s the unlicensed sub-letting of properties that hits the news; and with Facebook, the target was privacy breaches.

PayPal was targeted by banks for its risk and lack of security (falsely); M-Pesa saw incumbent banks saying they were fraudulent (falsely); whilst bitcoin created its own mess with Mt.Gox.

Meanwhile, we are now seeing the target phase for Fintech, as US banks hope to stop the march of Fintech through regulation. In August, the Clearing House produced a white paper that effectively said that the world of Fintech or, as they call them Alternative Payments Providers (APPs), is a Wild West.

Banks are subject to extensive regulatory, supervisory, and enforcement scrutiny by their regulators with respect to privacy and data security, APPs, by contrast, are providing their products and services by continuing to rely on the backbone of existing bank payment systems while capitalizing on innovations in communications platforms, thus generally managing to avoid the reach of the traditional financial regulators. Additionally, APPs only face punishment for lax data security practices if they suffer an actual cybersecurity breach that is discovered by the government, because unlike banks, APPs are not subject to regular examinations and enforcement actions by regulators.

What is key in this process is that you will always get an attack phase in innovation, where the disruptors become the targets of the incumbents before they become incumbents themselves. And yes, you guessed it, the Fintech unicorns are becoming incumbents.

I realised this when I watched SoFi and Lending Club presenting in a bank conference recently and they said over and over that banks are their partners; that they are serving underserved markets; that their operations were being funded by banks; and that banks are their preferred targets for partnership.

Talking with P2P lenders in the UK, they’ve had lots of regulatory to’s and fro’s but the key call here is that Zopa wanted regulation. When the regulations were introduced for P2P Lending by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in April 2014, the upstart made clear that they wanted regulation:

“Zopa has been lobbying for regulation for a number of years and was a founding member of the trade body P2PFA which has been successful in securing regulation for peer-to-peer lending.”

I’ve heard the same from several other Fintech start-ups, and the reason for the demand for regulation is that it makes the start-up trusted and respectable. My assertion of people not wanting to deal with untested and unlicensed firms is that, once they are tested and licensed, you can trust them. That’s why Zopa wanted P2P regulation. As Giles Andrews, CEO of Zopa (and guest of the Financial Services Club as keynote on November 25) states: “there is still faith that regulated industries are more trustworthy than unregulated industry”.

As startups become regulated, they are now able to move into the mainstream. By way of example, Zopa is now partnering with banks like Metro Bank, and being officially recognised as a Government supported tax-exempt savings vehicle by the Treasury.

The result of the innovation cycle is that, as the upstarts become incumbents, a new hybrid model appears. This hybrid model is where the upstarts integrate with the incumbents to become the incumbents themselves. I can see this happening already out there. For example, BBVA’s Innovation Centre recently reported on a debate with Fintech in Spain that ended with the headline: Fintech companies ask banks 'to collaborate, not compete' in the digital banking age.

The Economist also believes in this hybrid model. In a June article titled Why fintech won't kill banks, a key paragraph underscores why the developing model is a hybrid:

Many fintech groups do business in the billions, but banks often deal in trillions. Banks have ingrained advantages, not least the ability to create credit more or less at whim. And banking incumbents do some things remarkably well—notably the current account, which allows people to store money in a way that keeps it safe and permanently accessible. Few in Silicon Valley or Silicon Roundabout want to take on that heavily regulated bit of finance. Many admit they depend on it: after all, you need a bank account to use most fintech services.

According to CB Insights data, six of the largest US banks have made strategic investments in more than 30 fintech companies since 2009. A recent Accenture study found 60% of London investors are open to sacrificing current revenue in order to move to new business models and 80% see working with fintech startups as a valuable way to bring new ideas to their business.

And American Banker notes that the Fintech firms want these hybrid collaborative models. René Lacerte, Head of Paperless Bill Payment Service Bill.com, predicted a coming boom in marriages between startups and banks. “Traditional banks can bring much needed scale, resources and institutional clout to the table for young Fintech companies”, he says, and I agree.

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...