I recently had a great conversation with the head of innovation at a bank. In the middle of the conversation, we got into a discussion about how to get rid of complacency in the management team. The fact is that this bank is doing well. It’s growing its customer footprint, cross-sell ratio, account holdings, deposits and credit markets. Everything on the charts is heading up, including profits. Why would a bank like this decide to decimate branches, invest all in digital and reorganise around customers (rather than products)?

This is the challenge I get quite often, as my message is that you do need to decimate branches, invest all in digital and reorganise around customers. Hmmmmm …

OK, here goes.

Everyone is talking finance on technology and technology in finance. There is a difference in these two camps however.

The former camp talking finance on technology are, for me, the fintech community. This community believes they can rebuild banking and finance for the 21st century by internet-enabling money. This community believes that the old model of banking and finance from the 20th century is too difficult to internet-enable, and needs to be rebuilt.

The second group, talking technology in finance, are the financial community. This community believes that banking and finance needs to adapt to the demands of 21st century technologies, but are firmly grounded in their existing incumbent views. That incumbent view is that they can keep up by partnering with innovators, investing in front-end developments and maintaining interest in, but not necessarily adapting to, the new models of fintech.

The reason why I distinguish between the two groups is that you then have two tribes. Let’s switch from talking of them as communities. Let’s talk about them as two tribes as, when two tribes go to war, a point is all you can score. For those who don’t recognise that line, it’s the chorus of an old hit from the 1980s about the Cold War between the USA and Russia.

Is fintech and finance a Cold War or a collegiate? That debate is for another day, but the reason I want to position this as a Cold War today is that the two tribes are in a battle, just that one doesn’t see it that way. This then gets into the question of how to wake up the incumbent tribe.

So imagine that we’re a large City in medieval times. There’s a Village one hundred miles away. The Village is insignificant, and the City is not aware of the Village. That’s unfortunate, as the City has seriously pissed off the Village. That’s because the Village sent a group over to the City a few years ago to ask for help, and the guards of the City told the Village to get lost.

As a result, the Village went somewhere else for help and, luckily, they found it in the Lords of Anarchy. The Lords of Anarchy lives in a town far away. They had also heard of the City as being a law unto themselves and offered the Village men, money and weapons.

The Village recruited more and more capability thanks to this support, and rounded up other villages and towns against the City. Eventually, they became a serious threat as they overthrew the City and took over the lands.

Is that how fintech (the Village) is going to play out in finance (the City)?

It will be if the financial community or, rather, your financial institution seriously believes that digitalisation and fintech is no threat. After all, in our story above, the Lords of Anarchy would the venture capitalists pumping billions into the fintech dreams, which brings us back to the conversation the other day about how to wake up the management team.

This financial institution, like many others I meet, sees the Village as no threat. They have growth, profits and happy bonuses, just as Nokia and Kodak executives did a few years ago. There is no burning platform in their eye, so why should they do anything radical, especially as most of them will have retired by the time any of this hits the fan?

So, finally, here’s how I think the burning platform emerges.

Banks and insurers are technology companies. They are not seeing technology in finance, but need to rethink to be finance on technology (fintech). The key difference is that the latter is subject to the network effect.

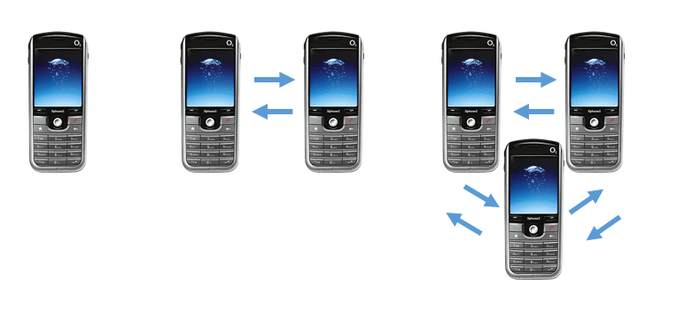

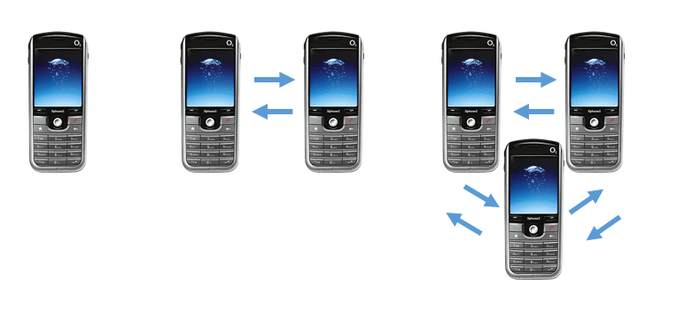

The network effect is well known, since the telephone was first invented. The network effect means that, as each device is added to the network, the connections are multiplied. Therefore, 1 phone = 1 connection; 2 phones = 2 connections. But then, as you add a third, the network effect kicks in as there are now multiple communication links that creates 6 connections: you to me, me to you, you to third person, third person to you, me to third person and third person to me.

This network effect ramps up over time, such that each new connection adds greater and greater connectivity adds greater and greater value. In other words, the network effect sees an increase in the value of goods and services as the number of users multiplies. This network effect was first cited in 1908 by Bell Telephone, but the mobile internet has amplified this effect massively. In fact, it leads us to network economics. Network economics leverages the network effect to create trade and commerce, and is the reason why we see mobile social as a critical marketplace today.

Mobile social allows everyone on the planet to share everything instantaneously. Viral is the word, and allows a selfie from the Oscars to be seen by a billion people in seconds. Ellen De Generes’s selfie was retweeted over two million times during the 2014 Oscar ceremony and has, by now, probably been seen by most people who have any awareness of the Oscars.

And this illustrates the internet of value well, as the mobile telephone used to take this selfie was a product placement by Samsung. So how much was that worth? A selfie that could be shared by a celebrity for free on the mobile internet of value? About a billion dollars, according to Maurice Levy, a marketing representative for Samsung. Maurice’s team handled the product placement of the Samsung phone used to take the selfie and a month later he was presenting at a marketing conference and said that Samsung had worked out that the photograph is worth $1 billion for the company, thanks to the millions of people who viewed the tweet and saw the photo being taken during the Oscars.

That’s the network economics and the network effect in action, and clearly illustrates the internet of value where a billion dollar moment takes place for free in real-time, globally. The global mobile internet where we are all connected is changing the game fast, and is the core tenet of the ValueWeb.

"Network effects is the term given to systems in which the value of each user is increased as the number of users goes up. Such network effects are common on the internet; for example, eBay and Facebook. The value of some such systems is roughly in proportion to the number of connections between users, meaning that if the user base doubles, the value of the system quadruples. This also acts as a barrier to new competitors, since new users are much more likely to join your system than a smaller one that doesn't offer the same value. If your company believes it will able to leverage such network effects, it often makes sense to treat the first users as a loss leader and get big as fast as you can."

- Tom Murcko

Back to banking. If banks believe they can continue with products sold through channels using traditional media and haven’t woken up to the network economics of fintech, then they will surely die. A long, slow, cruel death, but they will die. That is what happened to Nokia and Kodak, and will happen to your financial institution if the executive team are not taking digital seriously, not streamlining branch operations and not organising for customer-centricity.

The reason is that network effect competition can decimate markets. It’s never overnight, but it does over time. For Kodak and Nokia it was over a decade. For banks, it may be two, but it will happen if the bank does not change, as the network economics are obvious.

You can see it in peer-to-peer lending in the UK where, last year, the total value of P2P lending and crowdfunding amounted to £1.2 billion, taking total lending by the industry to £2.18 billion, more than double the figure at the end of 2013. It looks likely to double again this year and, based on Zopa’s forecasts, will continue for the foreseeable future. Zopa themselves have seen year-on-year doubling of cumulative lending for the past five years. Press release from August 18:

Zopa is first UK P2P lender to break the £1bn lent milestone as P2P goes mainstream

P2P pioneer sees 122% growth in loans for July compared to 2014

Zopa becomes the UK’s first P2P lender to lend £1 billion, helping over 200,000 people financially by getting a better value loan or growing their money. Consumers are now fully embracing non-traditional services that bypass the banks, with over half (53%) of UK adults saying they have lost trust in banks but still use them due to lack of alternatives available. This number rises to 62% of those aged over 55.

This lack of trust in banks has helped drive Zopa’s rapid growth as it has more than doubled (122%) its loan volumes in July, lending over £52m compared, to £23.5m during the same month last year. Zopa now has a 2% share of the UK unsecured personal loans market. The business has already matched more loans in 2015 than it did in the whole of 2014, and it expects to lend in excess of £550m in 2015, more than doubling 2014’s total of £265m. Revenues are also set to more than double for 2015 while credit risk performance continues to come in better than expectations.

Hmmm. That sounds like a burning platform as network economics hit the lending industry.

Same with Venmo. Venmo’s processing power is doubling year on year ($700 million processed Q3 2014 vs $1.6 billion Q2 2015). In fact, through fintech attacking payments and credit markets, there’s a strong likelihood that, in ten years, a significant part of bank profits and margins will have moved to new start-up companies.

So the bank has to adapt within ten years to be more like a fintech firm. Maybe sooner.

A final thought on complacency, which I’ve heard from a few bankers. They have this view that they already have millions of customers who are unlikely to switch to alternative providers that are untrusted, unproven and unlicensed. OK. That is the luxury of today that will give you the ten years to change and adapt without losing overnight. That is your cushion of today.

People do switch allegiances over time, especially if there is a better offer that is cheaper, more transparent, more convenient and easier to use. Think how fast things change. Ten years ago, taxi drivers felt secure, Nokia and Blackberry ruled the world, Washington Mutual and Royal Bank of Scotland were the most respected banks in the world and China was irrelevant. A little bit different today.

So, if you’re building your financial institutions strategy, there is a burning platform out there no matter how secure you feel. That is why I would much rather work in a bank with a CEO like Francisco González Rodriguez. Francisco González Rodriguez is the Chairman and CEO of BBVA, and he began life as a computer programmer. It is rare to find a bank led by a geek but this is one, and Mr. González knows how to lead his bank into the fintech age. From the Financial Times:

The BBVA bank vaults that hoard data instead of bullion

The processors, roughly six feet tall, huddle in subterranean corridors. Apart from their humming, the room is locked in something close to silence.

More commonly filled with gold, the vaults of banks now store data too. These processors inhabit the digital vaults of Spain’s Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria — its 20,000 sq m data centre on the outskirts of Madrid.

The building is a practical necessity, processing hundreds of millions of transactions a day. But the centre — and the data coursing through its veins — is also closely linked to BBVA’s vision for the future.

Spain’s second-largest bank, which has a major presence in Turkey, Latin America and the US, has established itself as one of the most ardent disciples of digital transformation. Between 2011 and 2013, it spent an average of €850m a year on investing in technology, infastructure — such as data centres — and software development.

It has also invested elsewhere. Last year it bought Simple, a US digital bank, and Spanish start-up Madiva Soluciones . Most recently, it invested in Coinbase, a bitcoin platform based in San Francisco, becoming one of the first mainstream financial institutions to make a play involving the controversial cryptocurrency.

“We’re embracing the disruption, to play a part in it, actively lead it,” says Teppo Paavola, BBVA’s head of new digital businesses. He was hired from PayPal and recently moved to Madrid from San Francisco. “In the end, what will the bank of the future be? All about data.”

In an article published in MIT Technology Review last year, Francisco González, the bank’s chairman, provided some insight into the specific value of data for banks. “Banks hold huge stores of information about their customers, and this is a crucial competitive edge,” he wrote. “If banks can convert that information into knowledge, they can use it to offer customers goods and services that better meet their needs.”

In the future, BBVA can potentially draw on data from millions of customers — 9m of the digital variety at the end of 2014 — to fuel what it calls “open innovation”, building new applications and services. Mr Paavola points out that this data will not personally identify any individual customer or business because it is all “aggregated and irreversibly dissociated” — meaning it can only be used en masse.

These technology platforms are bringing about a very deep change in how we do things, and how we process data and where we process data

- Francisco González, chairman, BBVA

The digital obsession is on clear display at another of BBVA’s centres, back in the noisier heart of Madrid. The bank’s innovation centre, which it describes as a “laboratory for testing new products and services”, also serves as a hyperactive promotion for the bank’s digital ambitions — the opposite of the data centre’s solemnity.

The innovation centre is housed in an elegant Madrid building, which, in former lives, acted as a prison, a palace and slaughterhouse. Nowadays, with 16,000 visitors a year, it resembles a corporate theme park, with designs depicting the future of banking, such as a full-sized model branch. A three-dimensional, pulsating map of Madrid sits alongside screens furiously flickering with Twitter followers, LinkedIn connections and Facebook likes.

Through the map, BBVA can display data about transactions through any of its cards or ATMs across the city — an approach it terms “urban radiology”. It can use this data, it says, to provide businesses with information about consumer habits — showing which parts of the city see higher volumes for certain types of purchase, for example, or how events such as football matches can determine consumer behaviour.

The bank is also reshaping itself as a kind of patron for financial technology, or “fintech”, companies, many of whom visit its innovation centre. It has multiple channels for working with technology, including BBVA Ventures — its San Francisco-based venture capital arm.

Many of its investments hinge on maximising exposure to world-changing technological breakthroughs. When the bank invested in Coinbase, Jay Reinemann, executive director at BBVA Ventures, said it simply wanted to “understand what was going on”.

The logic behind working extensively with other companies is based on the assumption that BBVA is unable to innovate as quickly as the collective mass of fintech start-ups, which also explains the bank’s appetite for acquiring smaller companies. “One of the things I’ve learned is innovation usually happens elsewhere,” says Mr Paavola.

BBVA even hosts X Factor- style competitions for tech companies; its Open Talent competition in 2013 was won by Traity, a Spanish company that seeks to help define reputation on the internet. The company now provides consulting services to the bank.

Its Innova Challenge provides anonymised credit card data to innovators around the world, which they can then use to create apps and services. BBVA rewards the best ideas in the competition with cash prizes.

In Spain, BBVA is not alone in its enthusiasm for technology. In recent weeks, for instance, rival Santander has announced a major digital push, including cloud-based services. Caixabank, the country’s third-largest bank, set up a “big data” centre in Barcelona last year.

But none of them has pushed as hard as BBVA. Behind the bank’s digital obsession is Mr González; the chairman suggested at a results conference in February that the bank will, in the future, become “completely digital”, adding: “These technology platforms are bringing about a very deep change in how we do things, and how we process data and where we process data.”

Typically, BBVA’s strategic involvement in other technology companies have not been accompanied by much financial disclosure, as though their value lies more in a declaration of digital intent. This month, however, it said “digital transformation” and associated cost management would yield annual cost savings of €340m in Spain.

The bank is building another data centre in Mexico. It expects to eventually have a total of four, processing 1bn transactions a day by 2016. The digital vaults might be less conspicuous than BBVA’s all-singing all-dancing innovation centre, but their scale and scope is growing.

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...