I often hear the lament from bankers that their business is designed around products, rather than customers.

They have been built upon product silo’s, where customer consistency of experience and interaction falls through cracks.

As you look at processes, the hand-off between a customer with a deposit account to their mortgage account, their cards, their loans, their savings, their investments and so on are all segregated, separated and difficult.

Why is this?

What is the reason why any company would organise around product rather than customer?

Well, according ot an article I stumbled across recently (thanks to @tomgroenfeldt), it’s all McKinsey’s fault.

Yes, that esteemed consulting firm who really understand strategic issues and requirements.

And yes, the firm that often falls foul of strategy when they get it wrong, which is more often than you think.

For example, McKinsey are to blame for over-inflated CEO pay levels, according to a book published last year by Duff McDonald titled: The Firm: The Story of McKinsey and Its Secret Influence on American Business. In an article in the New York Observer, he summarises the book as follows:

“The point is, when McKinsey embraces an idea and wholeheartedly pushes it on its clients, it tends to become widespread. And there’s no denying that this is what happened with Mr. Patton …

“In 1951, General Motors hired McKinsey consultant Arch Patton to conduct a multi-industry study of executive compensation. The results appeared in Harvard Business Review, with the specific finding that from 1939 to 1950, the pay of hourly employees had more than doubled, while that of “policy level” management had risen only 35 percent. If you adjusted that for inflation, top management’s spendable income had actually dropped 59 percent during the period, whereas hourly employees had improved their purchasing power …

“He published one of his findings in Men, Money & Motivation: a CEO’s compensation tended to increase with the size of a company. Unsurprisingly, CEOs have been gung-ho about M&A ever since. Another finding: in the 1940s and 1950s, the No. 2 man at companies made an average of 55 percent to 60 percent of the CEO’s pay, a “spread” that Mr. Patton considered totally reasonable. Mr. Patton was also involved in studies that showed that companies that paid bonuses boosted profit twice as quickly as others over a 10-year period versus non-bonus-payers. You can’t make this stuff up, people. Or maybe you can …

“Mr. Patton was arguably one of the first management gurus, a guy asked for by name, and after he retired from McKinsey, he was named chairman of a presidential commission on legislative, judicial and executive branch salaries in 1973. Even the government wanted a piece of that action! But so did everyone—then and now. Indeed, once started, the demand to increase and justify executive compensation became a perpetual motion machine that’s still chugging along.”

And the blame for product rather than customer focus?

According to Capital Flow Watch this dates back to the 1960s when Walter Wriston, the then CEO of Citibank, asked the management guru Peter Drucker how to make the bank more efficient. Drucker suggested that he contact McKinsey & Company to undertake a restructuring of bank management.

The motive was innocent enough:

Large clients, like the big oil companies, didn’t like to deal with branch managers who also served small clients and individual depositors. Big corporations wanted to be treated with deference. It was a marketing problem.

The solution was a complete reorganisation of the largest international bank. The McKinsey study took fifteen months and implementation began on Christmas Eve 1968. The process lasted for years and changed Citibank forever.

The essence of the McKinsey recommendations were simple enough:

- The bank should be reorganised along marketing lines, with different divisions for each major “product line”. (Before McKinsey, no one in Citibank referred to loans or deposits as “products”. After all, a bank wasn’t a manufacturing plant.)

- Because different kinds of clients used the commons services of the bank, like its branch network and back office processing, the “product line” organisation would have to be imposed on top of the existing structure. This called for a “matrix organisation” in which bank officers reported to different “product managers”. In effect, bankers now had multiple bosses.

It took about a decade for the McKinsey recommendations to be implemented and, In the process, the Citibank tradition of creating bankers with lifelong loyalty to their profession and to the bank was dead. Citibank had become a marketeer of industrialised financial “products” dedicated to short-term profits, run by managers rather than by bankers.

Soon enough, profit-oriented Citibank managers discovered another way to get ahead — they could invent new products that could be transformed into profit centres that they could manage.

Since Citibank was an international organisation, Glass-Steagall Act restrictions against engaging in investment banking could be circumvented in offshore operations.

This provided an even greater variety of financial products to market and added more complexity to the matrix organisation.

Finally, Sandy Weill took over Citibank and the culture of the old-time professional banker was gone forever. The bank had now become, in part, an insurance company and much more, with even more products to add to the matrix organisation. On top of organisational complexity, the bank now had problems with mismatched computer systems and conflicting organisational manuals.

By adding new products and focusing on short-term profits, Citibank inspired other large banks to follow their leadership. By adding new products and accepting ever greater risk, the bank grew and drew others down the same path.

By the 21st century, the original McKinsey banking heresy, which had started as what seemed to be a simple marketing makeover, had infected the whole world. This is because Citibank was, at the time, the world’s premier banking organisation. What Citibank did was eventually copied by Chase, Bank of America, and other large banks throughout the world.

So this is why banks are organised around products rather than customers, and why CEO pay far outstrips average worker's pay.

But it does not stop there. According to many writers, McKinsey leads their brethren in creating strategies that are wrong.

As Barry Ritholtz so eloquently puts it: No consulting firm that has been around as long as McKinsey has a blemish free record. But the total number of clusterfucks and McKinsey foibles they are associated with goes on and on.

Ritholtz points out that whenever there has been a financial disaster in the world, somewhere in the background McKinsey & Co is nearby.

He cites a number of examples where this is the case:

- Advocating side pockets and off balance sheet accounting to Enron, it became known as “the firm that built Enron” (Guardian, BusinessWeek)

- Argued that NY was losing Derivative business to London, and should more aggressively pursue derivative underwriting (Investment Dealers’ Digest)

- General Electric lost over $1 billion after following McKinsey’s advice in 2007 — just before the financial crisis hit. (The Ledger)

- Advising AT&T (Bell Labs invented cellphones) that there wasn’t much future to mobile phones (WaPo)

- Allstate reduced legitimate Auto claims payouts in a McK&Co strategem (Bloomberg, CNN NLB)

- Swissair went into bankruptcy after implementing a McKinsey strategy (BusinessWeek)

- British railway company Railtrack was advised to “reduce spending on infrastructure” — leading to a number of fatal accidents, and a subsequent collapse of Railtrack. (Property Week, the Independent)

And there are many others (just read Dangerous Company: Consulting Powerhouses and the Companies They Save and Ruin or Rip-off!: The Scandalous Inside Story of the Management Consulting Money Machine if you want to know more).

Add on a healthy dose of insider trading and greed, and you might wonder if what ails our industry and business in general is not our own mistakes, but following the lead of those who are mistaken.

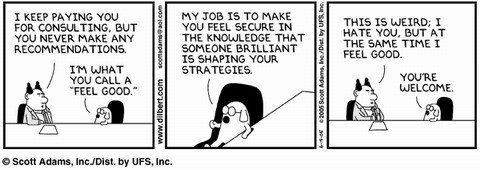

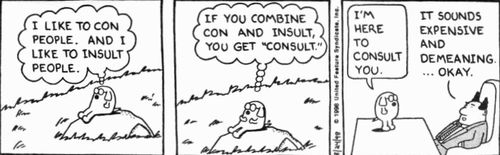

Dilbert cartoons stolen from Cominvent and Netzflocken

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...