The three blog entries on this subject so far:

- The African bank crisis and remittances

- More on Africa, Somalia, remittances, Barclays and

HSBC - Banks

should not be political pawns

has stirred up a lot of interest. In particular, Mondata, an American

consulting firm on mobile finance, has written a fascinating insight on the

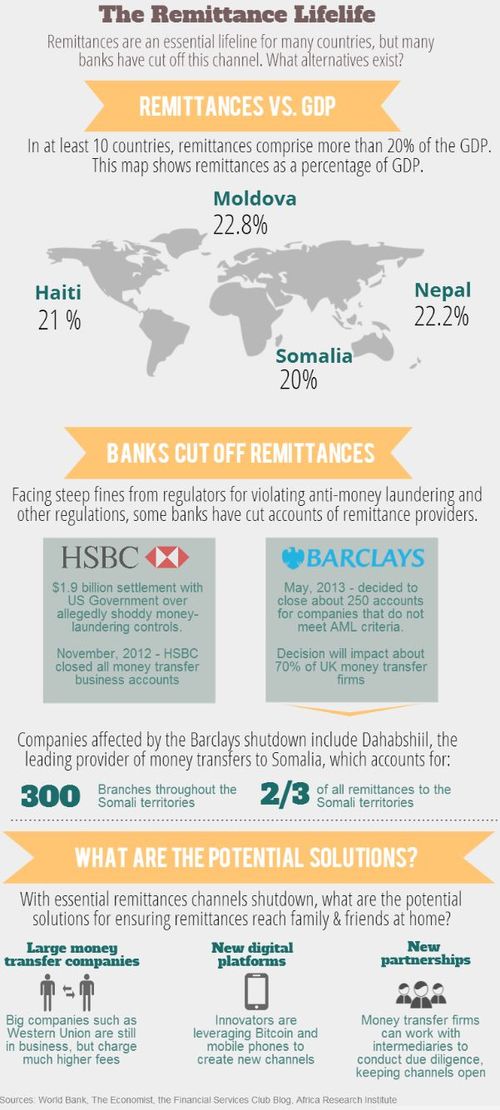

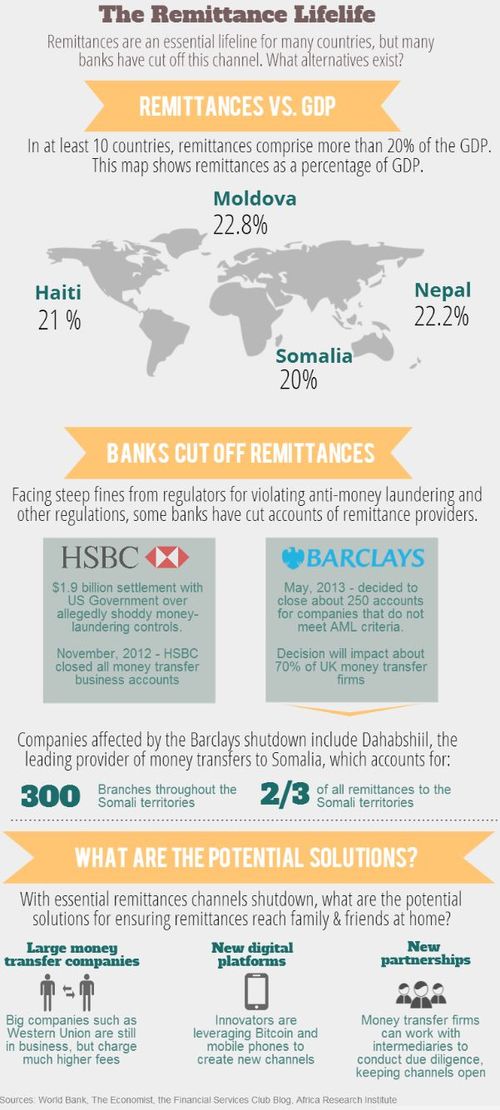

subject including this infographic:

In the spirit of keeping the conversation going, here’s

their analysis.

As Banks Cut

Lifeline, Will Remittance Alternatives Emerge?

In May, Barclays served notice that it would close the

accounts of approximately 250 companies that no longer meet its anti-money

laundering criteria, of which about 80 are active in the remittance sector. As

money transfer firms protested the decision, Barclays issued a statement that

it was concerned that, “some money service businesses do not have the proper

checks in place to spot criminal activity and could therefore unwittingly be

facilitating money-laundering and terrorist financing.”

As this decision gradually goes into effect over the next

few months, affected small- and medium-sized money transfer businesses may be

forced to shut their doors, lay off staff members, and sever essential

remittance lifelines to countries from Nigeria and Somalia to Sri Lanka and

Poland. What are the implications of this decision across the broader

remittance industry, and how might innovative solutions emerge to fill the

resultant gap?

Regulators v. Banks?

While Barclays is at the center of this current controversy,

it is not the only major financial institution to shift away from providing

accounts to international money transfer businesses. In fact, Barclays was one

of the last remaining British banks willing to provide these services. The

move, thus, is perhaps indicative of a broader, sector-wide problem. Facing

hefty Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT)

fines from US regulators, banks such as Barclays and HSBC are veering away from

the international money transfer space.

Last year, HSBC was forced into a US $1.9 billion settlement

by US regulators over allegedly poor money-laundering standards. Following the

settlement, HSBC decided to exit the money services business and close all

associated bank accounts, leaving money transfer companies with only 30 days to

find a new banking provider.

According to Dominic Thorncroft, Chairman of the UK Money

Transmitters Association (UKMTA), in a recent interview, there is no evidence

that the affected money transfer businesses do not comply with AML/CFT or other

regulations. However, this fact has not stopped regulators from increasingly

fining banks associated with these entities – forcing banks to withdraw account

services in order to avoid fines.

Cutting an Essential

Lifeline

Putting the reasons behind the Barclays decision aside, one

thing is clear: the move will have a dramatic impact on both money transfer

businesses and the recipients of remittances, many of whom are dependent on

this money as their primary source of livelihood.

Somalia will be particularly hard hit. Remittances comprise

over half of Somalia’s gross national income, with more than US $1.2 billion

remitted to the Somali territories annually. British-Somalis alone send up to

US $154 million (100 million pounds) each year, making up 60 percent of the

annual income of their families back home.

Dahabshiil, the largest money transfer business in the Horn

of Africa, is one of the companies that will be directly impacted by the

decision. According to CEO Abdirashid Duale, cutting off accounts to the

company and other money transfer agencies will be a “recipe for disaster.” His

company alone has nearly 300 branches and thousands of agents across the Somali

territories, providing an essential influx of money that is primarily spent on

food, medicine and school fees.

In Bangladesh, which received nearly US $1 billion in

remittances from the UK last year, the impact of the Barclays decision could be

similarly severe. According to Kamru Miash, managing director of KMB Enterprise

Money Transfer Ltd., about 80 to 90 percent of remittances from the UK to

Bangladesh go through Barclays’ accounts.

Pushing Back

Given the vital importance of remittances globally, the

question remains: how can money transfer stakeholders safeguard society from

money-laundering and the financing of terrorism, while keeping essential

remittance channels open? This is what UK Government officials, money transfer

industry associations, and members of civil society are currently trying to

figure out.

At the end of July, UK members of Parliament convened to discuss

how the Government could address the concerns of remittance companies. Members

of the Somali diaspora have also been particularly vocal in the discussion,

bringing their stories to the media. Further, a letter signed by more than 100

researchers and aid workers states that closing the Barclays Dahabshiil account

would cause a crisis for Somali families that rely on money transfers from

abroad.

According to Thorncroft, the UKMTA is meeting with

government officials, banks and other stakeholders to try to find a viable

solution. One proposed idea is to establish a code of conduct for money

transfer companies which would create an auditable set of standards for

mitigating AML/CFT threats.

What Are the

Alternatives?

With the Barclays decision primarily targeting small-scale,

local money transfer firms, industry heavyweights such as Western Union and

MoneyGram have seemingly escaped unscathed (even though they are responsible

for a large share of regulatory fines, according to Thorncroft). Thus, in some

contexts, diasporans may be able to use these services as an alternative.

However, using these platforms are often not a viable alternative, as they

charge far higher fees than local firms such as Dahabshiil. A simple comparison

of sending GBP 50 from the UK to Somaliland showed that Western Union fees (GBP

4.90) were nearly two times those of Dahabshiil (GBP 2.50).

In addition to offering less competitive exchange rates,

these companies may have less extensive branch networks, particularly in countries

such as Somalia. According to Duale, Western Union only has one branch in the

entire territory, located in Hargeisa, Somaliland – limiting accessibility to

the majority of the population. In Somalia, he says, “there is really no

alternative to using money transfer businesses."

Cutting off formal remittance channels, therefore, may

result in individuals seeking underground, unregulated alternatives. This in

turn could foster more money laundering, more terrorist financing, and more

crime, according to Thorncroft. UKMTA has estimated that as much as 50 percent

of existing cash-transfer business will divert to unregulated money transfer

providers, where supervision is near impossible.

Going Digital –

Mobile & Bitcoin

With a gap now emerging in the remittance market, perhaps an

innovative solution will arise to fill it. In a recent blog post on the

Barclays decision, co-founder of Project Diaspora and Hive Colab Teddy Ruge

asked, “is this an opportunity Africa’s mobile money revolution can exploit to

fill the gap?” According to Mike Laven, CEO of Currency Cloud, innovative “pay

out” solutions such as mobile money could make remittances more transparent,

assuring regulators that they are reaching the proper destination.

But, as Ruge asserts, “migrants can only send money home if

the regulatory environment in their host country allows it.” In practice, this

may also prevent any international mobile money transfer platforms from being

able to take off. One solution, according to Laven, might be for money transfer

firms to engage with intermediaries, who can conduct due diligence on smaller

firms – cutting down on AML and terrorist financing risks.

Perhaps Bitcoin, the decentralized, digital currency that we

wrote about here, could provide a solution. Kipochi, a Nairobi-based startup,

offers a Bitcoin wallet that enables users to easily send and receive funds via

the Bitcoin network. According to co-founder Pelle Braendgaard in a recent

interview, "we want to be the primary way to access Bitcoin for users in

the developing world." He said that he expects early adopters of the

wallet to include Africans and members of the diaspora who seek an affordable

and safe way to send and receive remittances.

Unlike traditional

money transfer firms, leveraging Bitcoin networks enables Kipochi to avoid AML

or other regulatory risks, as the risk liability falls on the third-party

Bitcoin exchange. This means that Kipochi can operate even in high-risk areas

such as Somalia, where many other companies either cannot or do not want to

offer services.

While pressure from

US regulators and international banks may be formidable, perhaps new players

such as Kipochi can break through the stalemate and offer a product that can

keep remittance channels open, while maintaining necessary checks against money

laundering and other threats. With many livelihoods dependent on these

remittances, it is essential that a solution be found, and soon.

Enhancing

Humanitarian Aid with Mobile Money

Beyond P2P remittances, international money transfers also

face limitations in the humanitarian aid space, where money often flows across

borders to provide support in conflict zones, areas with limited rule of law,

or to rebuild communities following natural disasters. For aid organizations,

sending money in these contexts can run into formidable operational and

regulatory barriers – and mobile money transfer has emerged as a potential

solution.

Money Transfer in

Challenging Contexts

It is in areas of conflict or natural disasters that people

are often most in need of outside assistance, whether from family members or

international aid organizations. These streams of income can cover the costs of

basic needs or help to rebuild essential infrastructure. However, money

transfer infrastructure is understandably weak in these contexts. Banks may be

far away from those in need, or even destroyed. Transactions can face a variety

of regulatory hurdles, and thus take a long time to be completed. In some

cases, aid organizations opt to deal with cash, which can bring risks and

inefficiencies for both senders and receivers, and can limit the accountability

of funds.

Opening Access with

Mobile

Facing these complex challenges, many aid organizations have

turned to mobile channels to enhance recipient access to funding sources.

Mobile disbursement of aid can enable cheaper, faster and more transparent

transactions.

In an interesting case study from Bangladesh, Oxfam and

bKash entered into an agreement to transfer cash to 3,371 households via mobile

channels, ensuring timely and secure payments to households most affected by

flooding in the Northwestern districts. According to a press release on the

program, “using bKash as a delivery agent will result in possible reduced

corruption and security risks, reduced workload of agency staff, and greater

flexibility for recipients.” Further, the document notes that the method is

particularly valuable during emergency situations, given the limited time it

takes to disburse money through the platform once it is up and running.

Haiti provides the classic example of the use of mobile

money in an emergency situation, where mobile money was used to distribute aid

following the 2010 earthquake – a project which highlighted both the advantages

and disadvantages of mobile aid disbursement (see this past Mondato article). While NGOs in

Haiti used four electronic money distribution platforms – mobile money,

electronic vouchers, prepaid cards and smart cards – mobile emerged as the

preferred option.

The recent partnership between Visa and NetHope provides

another example of how mobile money can be used in the humanitarian aid sector.

The companies have partnered to create the Visa Innovation Grants Program,

which provides five grantee organizations with funding to modernize their

payments systems.

One grant recipient, MercyCorps, is using the funding to

develop mobile money services for farmers or other actors in agricultural value

chains. Pathfinder International, another recipient, is implementing a mobile

money platform to distribute salaries to community health workers in Kenya.

Though these programs are not directly in emergency or conflict contexts, they

show how mobile money can be used to transfer aid funding directly to

beneficiaries in a transparent fashion.

Assessing Mobile

Money for Aid

Pilot projects that use mobile money for aid distribution

both highlight the benefits of using mobile money in emergency contexts, and

serve as cautionary tales for NGOs thinking of going this route. According to a

CGAP blog post from last year, early-stage mobile money ecosystems, such as

those that emerge for aid disbursement, may have inefficiencies that need to be

ironed out before the platform can function smoothly: “NGOs should take pains

to appraise all the costs of starting up a program based on mobile money,

including the possibility that they will have to help other actors build the

infrastructure of the industry.”

The Dalberg and Gates Foundation report that was produced to

assess the impact of mobile aid disbursement in Haiti offers key lessons for

other NGOs planning to integrate mobile money into their programs, particularly

in post-disaster situations. One challenge cited in the report was fulfilling

know-your-customer (KYC) requirements for new beneficiaries in areas where many

did not have official forms of identification. The workaround solution was

using mini-wallets with lower KYC requirements or agreements with MNOs to

accept NGO-issued ID cards.

Another challenge in some contexts is that, despite the

near-ubiquity of mobile devices globally, not everyone has a mobile phone, “let

alone an account linked to their phone which can accept fund transfers.” And

even if everyone did have a personal mobile device, it is likely that they are

not all operating on the same network. According to the CGAP post, therefore,

“until cell phones are truly ubiquitous, mobile transfers need to be weighed

against other options that may be cheaper or more practical for distributing

cash transfers.”

The Verdict?

Using mobile money in the aid sector holds promising

benefits over cash and other methods of transferring funds, particularly in

post-disaster areas or emergency contexts where funds need to travel quickly

and safely. Cross-sectoral actors, such as those involved in the Better Than

Cash Alliance, have endeavored to usher in the transition to digital payments,

but much more still needs to be done. However, as aid actors look to integrate

mobile, they will need to move cautiously and consider how this will fit into

the contexts in which they work – lest mobile money become part of the problem,

not the solution.

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...