I just had a quick tour of the British Museum inspired by an

article I read in The Telegraph about their exhibition of British bubbles and bankruptcies.

The exhibition traces back schemes from the 1600s,

such as the Darien Disaster, right through the Railway Mania and Overend and Gurney Bank failure of 1866 through to Northern Rock and the credit crisis today.

Here are the key disasters you can check out if you visit the Museum before the end of May.

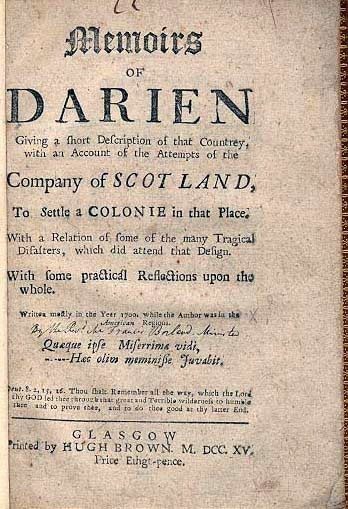

The Darien Scheme.

1700

The Darien Scheme, which became known as the Darien

Disaster, was a colonisation project that attempted by the Kingdom of Scotland,

which was a separate Kingdom at the time, to become a world trading nation.

The idea was to establish a colony called

"Caledonia" on the Isthmus of Panama in the late 1690s, and the

Darien Company was formed with £170,000 of investment (about £300 million in

purchasing power today), mainly from Scottish nobles and landowners.

From the outset, the undertaking had problems due to poor

planning and provision, weak leadership, a lack of demand for the goods traded,

devastating epidemics of disease and shortage of food.

It was also heavily opposed by the King of England, William

III, and other English rival trading companies, as well as those of France and

Spain. As a result, the Scheme was

abandoned in April 1700, after a siege by Spanish forces.

As the Darien Company was backed by nearly a quarter of all

of the money circulating in Scotland at that time, the nobles and landowners

were near completely ruined and was an important factor in weakening the resistance

to the Act of Union.

Not long after, the Scots lost the Battle of Culloden in 1746 and became part of the United Kingdom, or England if you want to be

really argumentative.

Source: The 10 Most Doomed Expeditions in History

The South Sea Bubble, 1720

In 1711, after a war which left Britain millions of pounds

in debt, the government proposed a deal with the South Sea Company to allow

Britain’s debt to be financed in return for a higher level of interest. In

order to sweeten the deal, the government added another benefit: sole trading

rights in the South Seas.

Because of their monopolistic position and strength with

government backing, shares in the South Sea Company were incredibly popular and

their value rose to ten times their initial public offering price.

Seeing the success of the first issue of shares, the South

Sea Company quickly issued more. Again,

the stock was rapidly consumed by the voracious appetite of the investors. Investors saw that the stock was going to the

stratosphere and they wanted in.

Equally, many investors were impressed by the lavish

corporate offices the Company had set up even though, at the time, they had not

even started trading in the South Seas.

The extent of the South Sea bubble can be seen by the fact

that 462 members of the House of Commons and 112 Peers had some sort of stake

in the South Sea Company. Everyone

bought into the stock.

Then the 'bubble' burst because people discovered that the

South Sea Company, after several years of trading, had yet to actually deliver

any goods or produce from the South Seas.

The shares had been valuable on paper, but worthless in reality. Hence, the herd mentality that caused this

madness of crowds suddenly sobered up and everyone pulled their money out of

the markets.

People all over the country lost all of their money. Porters

and ladies maids who had bought their own carriages became destitute almost

overnight. The Clergy, Bishops and the Gentry lost their life savings. The

whole country suffered a catastrophic loss of money and property. There was even a call in Parliament to

resurrect the Roman punishment of Lex Pompeii, where bankers and those involved

in this disaster would be tied in sacks with snakes and thrown into the Thames.

The South Sea Company Directors were arrested and their

estates forfeited and frantic bankers thronged the lobbies at Parliament.

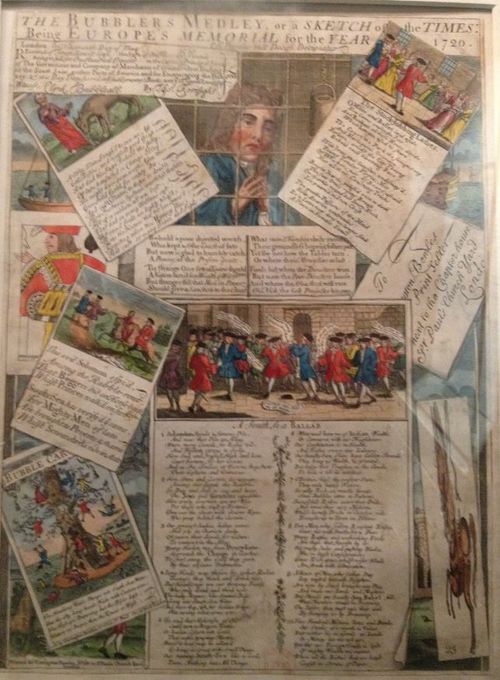

The Bubblers Medley, or a Sketch of the Times: Being Europe’s Memorial

for the Year 1720

The satirical print

shown here is a remarkably rich record of the popular culture surrounding the

South Sea Bubble in England and the Mississippi Bubble in France, both

occurring in 1720.

The France War Crisis, 1797

After the storming of the Bastille in 1789, France was

overseen by various coalition governments of revolutionary forces and, for over

ten years, created wars with other European nations in an attempt to gain

supremacy.

On 21st January 1793, the revolutionary

government executed Louis XVI after a show trial. Spain and Portugal entered the anti-French

coalition in January 1793, and, on 1st February, France declared war

on Great Britain and the Dutch Republic.

The war with France was extremely expensive, straining Great

Britain's finances.

Unlike the latter stages of the Napoleonic Wars, the war

effort was mainly operated by sea power and by supplying funds to other

coalition members facing France. This

meant that, in 1797, Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger was forced to

protect Britain’s gold reserves by preventing individuals from exchanging

banknotes for gold.

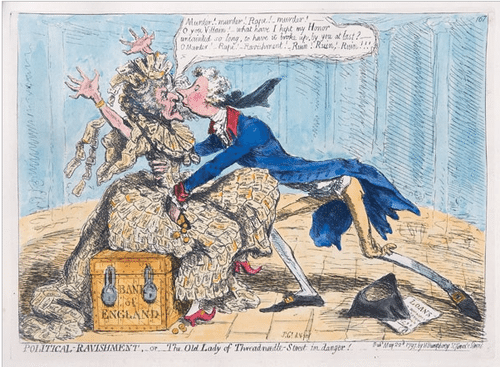

This led to one of the most famous cartoons in Britain’s history

of finance: the ravishment of the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street by Thomas

Gillray in May 1797.

The cartoon is a

reference to the financial crisis of the time and the issuing of paper money

not backed by gold, and shows William Pitt pretending to woo the Bank which is

shown as an old lady wearing a dress of £1 notes seated on a chest of gold. Britain

would continue to use paper money for over two decades.

Hence, the cartoon led to the Bank of England gaining

nickname the “The Old Lady of Threadneedle Street”*.

The Poyais Scam, 1825

Gregor MacGregor was a Scottish soldier, adventurer, land

speculator, and coloniser who fought in the South American struggle for

independence. Upon his return to England in 1820, he claimed to have been made

the Cacique (a Prince) of the Principality of Poyais, an independent nation on

the Bay of Honduras.

This nation was given to him by the native chieftain King

George Frederic Augustus I of the Mosquito Shore and Nation, and was the equivalent

of 12,500 miles² (32,400 km²) of fertile land.

At the time, British merchants were all too eager to enter

the South American market and MacGregor was welcomed by London high society. He also claimed that one of his ancestors was

a survivor of the Darien Scheme and, in order to compensate for this, he had

decided to draw most of the settlers from Scotland.

MacGregor established offices in Edinburgh and Glasgow,

selling land rights for 3 shillings and 3 pence per acre in 1822 (about £10 an

acre today).

Soon after, a “Sketch of the Mosquito Shore” including the

Territory of Poyais written by Captain Thomas Strangeways was released,

describing Poyais in glowing terms and boasting of the profit one could gain

from the country's ample resources.

Poyais was described as a very anglophile region with infrastructure,

untapped gold and silver mines, and large amounts of fertile soil ready to be

settled.

On 10 September 1822, the

Honduras Packet departed from the Port of London with seventy

would-be-settlers, including doctors, lawyers and bankers who had been promised

positions in the Poyais civil service. On

22 January 1823 another ship, the

Kennersley Castle, left Scotland for Poyais with 200 would-be-settlers and

enough provisions for a year.

The settlers found nothing and were left ruined and homeless

in a jungle full of diseases. They were found a year later by accident, and the

Chief Magistrate told them that there was no such place as Poyais, but agreed

to take them to British Honduras. By the time they arrived in British Honduras,

180 of the 240 would-be settlers had died or were lost.

The survivors departed for London on August 1, 1823, but more

died on the journey back such that fewer than 50 made it back to Britain alive.

When they returned, city papers published the whole story.

Astonishingly, some survivors refused to label MacGregor as

a culprit, but blamed his advisers and publicists for spreading false

information. MacGregor, however, had left for Paris in October 1823 where he

continued to peddle his schemes of riches in the Americas.

Over his lifetime , his bond-market frauds ran to £1.3 million (as a share of Britain’s economy,

around £3.6 billion today).

Take note however, that the Poyais Scam was just one of many

schemes that failed at this time, with frenzied investment culminating in many

bankruptcies. For example, over sixty

banks failed during the 1825 panic, leading to a chronic shortage of cash in

circulation in the economy and the Bank of England having to recycle old bank

notes to keep the economy running (sound familiar)?

Bank of England £1 Bank Note, Issued in 1821 and Reissued in 1826

Railway Mania, 1846

Another historical section focuses upon the Railway boom and

bust of the 1800s.

The Railway Mania was a speculative frenzy in Britain in the 1840s, and follows the usual pattern

of a boom bust cycle.

It began with the expansionism of the rail network across

Britain and, as the price of railway shares increased, more and more money was

poured in by speculators until the inevitable collapse.

It reached its peak in 1846 when 272 Acts of Parliament were

passed setting up new railway companies, and the proposed routes totalled 9,500

miles (15,300 km) of new railway.

Around a third of the railways authorised were never built

with the companies concerned either collapsing due to poor financial planning

or being acquired by a larger competitor before it could build its line or

turning out to be a fraud.

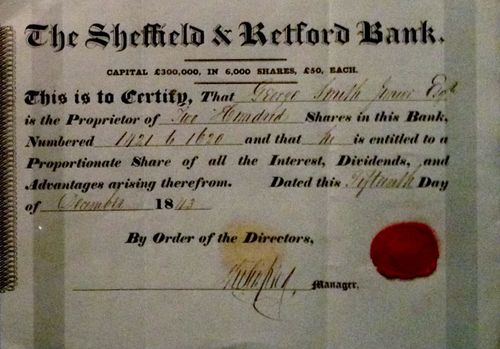

The Sheffield and Retford Bank Certificate 1843

The Sheffield and

Retford Bank arranged large loans to railway companies to finance line construction,

selling shares such as this to raise capital.

In 1846, a number of railway companies defaulted on their loan repayments,

causing the bank to fail.

Preface to the 1857 edition of Little Dorrit by Charles Dickens

I have been occupied

with this story, during many working hours of two years … I would hint that it originated after the

Railroad-share epoch, in the times of a certain Irish bank, and of one or two

other equally laudable enterprises.

The Overend Gurney

Crisis, 1866

Overend, Gurney & Company was a London wholesale discount bank, known as "the bankers' bank",

which collapsed in 1866 owing about 11 million pounds, equivalent to around £1

billion today.

The business was founded in 1800 with Gurney's Bank (acquired

by Barclays Bank in 1896) supplying the capital. The bank devoted itself

entirely to the buying and selling of bills of exchange at a discount which, at

the time, was a market only loosely served by other banks. The idea was novel

and proved an instant success and, for over forty years, it was the greatest

discounting-house in the world. During the financial crisis of 1825, the firm

was able to make short loans to many other bankers. The house indeed became

known as "the bankers' banker", and secured many of the clients of

the Bank of England (the Bank was not nationalised at this time).

The bank expanded its investment portfolio and took on

substantial investments in railways and other long term investments, rather

than holding short term cash reserves.

The result was that it found itself with liabilities of

around £4 million, and liquid assets of only £1 million. In an effort to recover its liquidity, the

business was incorporated as a limited company in July 1865 and sold its £15

shares at a £9 premium, taking advantage of the buoyant market during the years

of 1864-66. However, this period was followed by a rapid collapse in stock and

bond prices, accompanied by a tightening of commercial credit. Railway stocks

were particularly badly affected.

Overend Gurney's monetary difficulties increased, and it suspended

payments on 10 May 1866. A run on the bank ensued as panic spread across

London, Liverpool, Manchester, Norwich, Derby and Bristol, with large crowds

around Overend Gurney's head offices at 65 Lombard Street.

The bank went into liquidation in June 1866, and created a

financial crisis that saw over 200 companies and banks failing as a result.

The directors of the company were tried at the Old Bailey

for fraud, but were only found guilty of “grave error” rather than criminal

behaviour, and the jury acquitted them.

The exhibition then jumps forward to more recent crisis,

such as the crash of Barings Bank, Northern Rock and the most recent financial

crisis.

These are all well covered here on the blog, so I won’t rake

over those coals, but the interesting thing is that there are common themes to all

of these booms and busts, as regularly discussed here on the blog.

The core is that whenever you see a continual and major rise

in asset prices – shares, markets, industries, commodities, property, etc – it is

guaranteed to go bust at some point.

Continual rises in asset prices at a higher than average

level of expectation is unsustainable and will go bust.

Then, when it does go bust, there will always be a blame

game afterward.

Blame of individuals:

“Barings has been the

victim of losses caused by massive, unauthorised dealings by one of its traders

in South-East Asia.”

Barings press

statement, 26th February 1995

Blame of customers:

“Northern Rock was

pushed to the brink of extinction by savers withdrawing their money amid fears

that the panic could spread to other banks.”

Daily Mail, 17

September 2007

Blame of corporations:

“Bankers have made an

astonishing mess of the financial system.”

House of Commons

Treasury Committee Report, 2008-2009

Blame of regulators:

“We allowed a [banking]

system to build up which contained the seeds of its own destruction.”

Mervyn King, Governor

of the Bank of England, 5th March 2011

* There was a real Old Lady of Threadneedle Street: Sarah Whitehead.

Sarah had a brother

called Philip, a disgruntled former employee of the bank, who was found guilty

of forgery in 1811, and executed for his crime.

Sarah was so shocked she became 'unhinged' and every day for the next 25

years she went to the Bank and asked to see her brother.

When she died she was buried in the old

churchyard that later became the Bank's garden, and her ghost has been seen on

many occasions in the past.

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...