Giles Andrews, Chief Executive of Zopa, recently spoke at the Financial Services Club, London, and has kindly provided me with his script and slides to share with y'all so, here it is ...

Thanks very

much to Chris and Andy for asking me back and to all of you for coming to

listen. I hope most of you know a little

about what we do but, for those who don’t, here’s a slide that explains it

pretty simply.

By cutting

out banks we provide better value to consumers who are sensible with their money – lower cost loans on one side, and

better returns on their savings on the other.

Before I

prepared something for tonight I had a look at what I have said here before, on

the small chance that anyone would actually come and listen to me again. So I’m not going to talk about the origins of

the idea. I’m obviously happy to do that

over a glass of wine later.

Firstly, I’m

going to give you an update on how we’re doing; secondly, I want to talk about

innovation; and thirdly, and perhaps most controversially in this setting I’m

afraid, I want to talk about culture and its impact on trust. It may mean I’m not invited back, but I hope

not, as it’s meant to stimulate thinking and discussion!

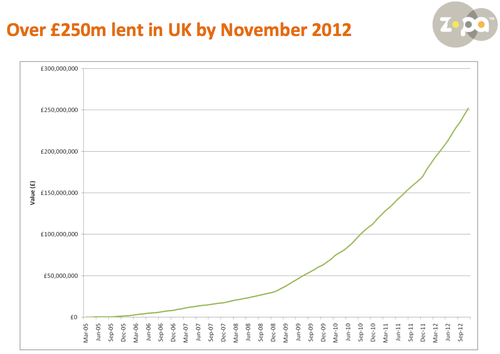

So now for

that update. Chris always wants to know

how we’re growing and I want to make some announcements tonight the first of which is

that we have lent over £250m now, or a

quarter of a billion pounds as my PR people tell me to say.

I’m jumping the gun slightly as we will

actually hit the milestone on Friday, but I thought I could get away with it in

this company.

So now we’ve

got that out of the way I’m going to talk about innovation. This has been an issue in financial services for

a long time, well before the crisis.

We all know

the story about the ATM being the biggest financial innovation in recent times.

As Paul Volcker, former Chairman of the US Federal Reserve, said in the Wall Street Journal, 8th December 2009: “...the most important financial

innovation that I have seen the past 20 years is the automatic teller

machine...”

That's it?

One of my favourite stories comes from a different sector and this one is relevant to banks when we think about genuine consumer value focussed innovation.

Forty years

ago, garage workshops were located (as they still are) in large, usually flashy

“general” dealerships in inconvenient places.

The

aftersales product sold (not the one customers thought they were buying) was

labour, and all jobs had a labour component.

These labour

charges were high, allegedly to support the highly trained mechanics and to pay

for the expensive facilities.

I understand

the top labour rates within the London area have now broken through £200 per

hour, or about the same as you pay a junior city solicitor or accountant.

The easiest

way to run these businesses was to organise a workflow from all the jobs of the

day and, as customers couldn’t be trusted to bring their vehicles in, to

organise that workflow once all the jobs were booked in.

That meant

all the customers dropping their cars off in the morning leading, of course, to

queues at the counter.

Customers

then had to somehow get to their place of work from the inconveniently located

dealership, only to have to repeat that mission at the end of the day, and pay

over the odds for often trivial work.

But someone

thought of a better way to handle part (importantly

not all) of this £8 billion UK aftersales market.

In 1971 a

young entrepreneur called Tom Farmer was on holiday in the USA, after selling

his first business.

He noticed

the “muffler shops” there with interest.

Some

aftersales jobs didn’t need skilled mechanics or smart facilities. Some

of the parts to be supplied had terrifically high margins and could be fitted

very fast.

The KwikFit

operation he started in the UK had a genuinely different business model.

They didn’t

seek to replace full service garages, but only to steal the bits of their

business they could do better, offering more convenience and better value to their customers.

Full service

garages now don’t sell any tyres or exhausts.

The whole

business worth over £1 billion per year - or 15% of their business - has gone, never

to be replaced.

The customer

gets to go to a convenient location on a High Street, at a time of his

choosing, while paying less for the service.

No wonder these

businesses enjoyed stratospheric growth and Tom Farmer became a very wealthy

man.

The parallel

with Zopa is that we have developed a lower cost model for a small part of

banking.

Why is it a

lower cost model?

We offer

unsecured personal loans and a simple savings or investment product.

Because the

loans are fixed length, we can easily match their maturities with the savings

product, and provide our lenders with a decent and predictable return. But we

couldn’t offer current accounts or credit cards, as we couldn’t pay our lenders

a return on unused facilities without becoming a bank with a complex treasury

function. Because the loans are

unsecured we don’t need lots of admin, and the resulting high overheads, to

manage the security.

In terms of

running the business, our job is to make sure that returns are safe and

reliable by screening the applicants and spreading each lender’s risk across

many different borrowers.

We have

therefore built most, but importantly not all, of the functions of a typical

bank, including managing credit and risk. And we have done that better than any other UK

lender, with defaults below 0.8% of the quarter

of a billion pounds we have lent to date. And we have done it profitably since 2011, so

are proud to be a self-sustaining business.

Now back to

retail banking.

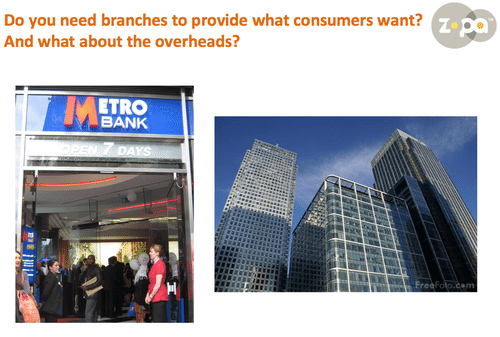

I keep being

struck by hearing bankers talking about the strengths of the branch model, and

the importance of their customer “relationships”.

I heard a

presentation by a high profile new entrant talking about the strong economics

of deposits taken by branches, as customers apparently value service and

relationship above rate.

So the

question becomes: how does that compete with a model that provides both service

and value?

We are told

of the “stickiness” of deposits taken at branches during the credit crisis

versus internet deposits like at ING Direct.

In other

words, banks treat branch customers as either stupider or lazier than online

banking customers, since they didn’t remove their funds to the same

extent.

So how about

addressing the problem of making internet deposits sticky, as we have by

matching the maturities of the savings and loan products, while saving the

costs of the branch network?

A recent

survey by the American Bankers Association found that 57% of customers over the

age of 55 prefer to do their banking online, yet banks continue to invest

vastly more in developing their branch offerings than their internet and mobile

channels, which are sub-standard in terms of service, perversely driving some

consumers back to the branches and reinforcing the delusion that’s what

customers want!

Our view is

that most consumers want value above all else, and I think the winners will be

those who focus on that and not a flawed “relationship”.

And that

brings me on to the subject of culture and its impact on trust.

We hear a

lot about banks needing to restore trust and that’s pretty well it. We don’t

hear about why they have lost it and what they propose to do about it. It’s as if the words are enough. It’s some kind of PR issue that they just

need to work through. Well, even if that

were the case, what are the golden rules for dealing with PR crises?

- admit the problem, in full, no weasel

words; - say sorry, you understand how people

feel; - say it may even get worse before it

gets better so you look really honest; - say what you are going to do about it;

and - say sorry again.

Compare that

to what have we had here: “There has been a global financial crisis (it’s not our fault); we understand that

has led to people not trusting us (nothing

about what they have done to cause that); so we recognise we need to

rebuild trust (nothing about how) … and

then everything will be back to normal.

Let me be

clear, this is not just a PR problem. It’s far more fundamental than that. I think it’s a culture problem not a trust

problem at its root, although the loss of trust is clearly a consequence.

Let me give

you a few examples.

I was kindly

invited to dinner with some leading UK retail bankers. I won’t name names but suffice it to say

there were UK heads of most of them. Our

host asked what they thought had caused the loss of trust, and they answered:

- the USA; and

- investment banks flawed business

models and misaligned bonus structures.

They were

very clear it was nothing to do with UK retail banking.

When I

politely mentioned PPI, the biggest financial mis-selling scandal in UK history

and entirely retail bank based, there was some nervous coughing and fidgeting.

Then would

you believe the answer?

It was the

previous discredited and now-departed management at their banks what done it.

The irony is

“now-departed” in these cases actually often meant to another of the banks in

the room, so in effect some of them were blaming other regimes in the room that

were also passing the buck!

You really

couldn’t make it up.

It was also

the previous sales incentives, now changed of course, although they did admit the

new ones were still commission or bonus based in large part.

I’m sure

those incentive structures did play a major part, but those structures were

driven by the culture of the organisation, and that culture somehow forgot the

importance of the customer!

Throughout

this period the FSA had a regulatory standard called “Treating Customers Fairly”,

which was evidently about as much use as a chocolate teapot in the face of the

overwhelming culture of profits at all cost.

Another

retail (or at least not investment) banking example, and I’m sorry to name

names here, is the “alleged” failure of HSBC to perform reasonable anti-money laundering

checks in Mexico and, rather closer to home, the Channel Islands, resulting in

it “allegedly” dealing with known criminals.

Or from our

very own Chris Skinner’s fine blog recently, their decision to exit the Money

Services Business with only 30 days notice, not giving long standing customers

the chance to find alternatives.

Or ING

pulling out of equipment leasing at a few days notice.

At least that

was to the benefit of one of my P2P colleagues Funding Circle, but again with no

thought to customers.

Or to move

to investment banking, perhaps the clearest example of forgetting the customer

is the enormous conflict of interest caused by betting against your own

customer in the derivatives markets, for which major banks have accepted fines

if not blame.

Back to my

PR crisis lesson, everyone really knows they did it. And do I need to mention LIBOR?

So what to

do?

Firstly,

challenge the assumption of economies of scale.

I commend to

you an article in the Economist a couple of weeks ago challenging the

assumption across many industries, with banking at the forefront.

I would

assert that the economy of scale “enjoyed” by the big banks was all to do with

funding costs and look where that got us: cheap money looking for a home in

ever bigger bets...

The mistake

is now being repeated by governments and, if you strip it out, I think you

would find the big banks are less and not more efficient.

If this simple

business fact was transparent, the egregious “too big to fail” problem would go

away of its own accord, stimulating more competition.

For

consumers and tax payers, what’s not to like about that?

Indeed Andy

Haldane (he’s a fan of Zopa and P2P by the way, as mentioned in the invitation

tonight) said recently he would set the cap at a surprisingly low level versus

Barclays and RBS balance sheets of £1.5 trillion.

Secondly,

challenge the assumption of cross border economies.

With the

exception of a handful of global equity and fixed income trading businesses,

and some outliers like VISA, MasterCard and PayPal, I don’t think there’s much

positive evidence for them.

That removes

the business case for most of the “bulge bracket” investment banks, again

helping to solve the “too big to fail” problem.

Maybe the

old partnership model that was dispensed with in the pursuit of scale was

simply better?

Thirdly,

banks need to actually do something positive about addressing their culture. My contention is that they haven’t to

date.

They could

start by designing products and services that provide genuine value, put the

customer and not their P&L first, that customers like and tell their

friends about.

I’m not

advocating some kind of altruistic nirvana, as some of the most successful and profitable

companies put customer enjoyment and experience first. Apple and Zappos spring to mind.

I’ll never

forget a lesson from my first job, which was that the customer pays my wages.

I’m not

going to get into the regulatory debate, there are others much better qualified;

suffice it to say that I hope, perhaps unrealistically, that the banking review

does lead to increased competition. And

I do expect P2P lending to be regulated one day.

I’m happy to

discuss that further in Q&A if anyone is interested.

So where

does that leave Zopa and our growing P2P sector?

I hope I

have made the case for increased efficiency through a narrow business

model.

I was at

another dinner recently, this time hosted by Chris Skinner, where the most

common question was “can it scale”?

I believe

that the efficiency of our business model will allow us and our competitors to

scale in our particular sector more than the banks – now there’s a

promise!

Fortunately

we aren’t the only people to believe it, so I’m delighted to make my second

announcement of the night: now that we have proven all aspects of the model –

it provides great value to our savers and borrowers, profitably for us - we

have secured a new round of multi-million pound funding through equity investment in Zopa to help scale and

critically to build awareness of our business.

Thank you.

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...