I mentioned I was in Iceland last week, and was interested to find out what the banks were thinking.

We only ever hear of Iceland’s woes and troubles, and so the ability to see first-hand what was happening to the banks was one that could not be ignored.

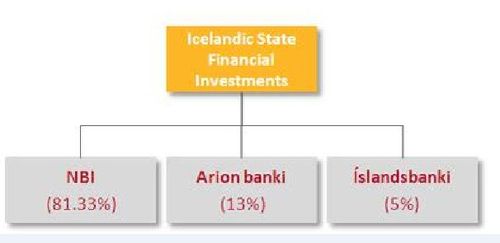

According to Wikipedia, there are only a few commercial banks left in Iceland: Arion Bank, Byr, MP Bank, NBI and Íslandsbanki, although their information is slightly wrong as they list Landsbanki as defunct whereas the bank is still running well, admittedly 81% owned by the government.

In fact, it’s very easy to get things wrong, as highlighted by Deena Stryker’s article to which I referred last week.

I also got my own sums muddled, as I thought Landsbanki was privately held still, but it’s not. It’s majority owned by the Icelandic government, unlike Íslandsbanki and Arion Bank who are 5% and 13% government owned respectively.

In other words, the Icelandic banking system is not dissimilar ot the UK or Ireland or others in the EU, where governments have had to subsidise their banks to avoid complete collapse.

Similarly, as outlined in the document that refuted Stryker’s article, Iceland is not bankrupt or dead. It is still severely challenged, but then aren’t we all?

So, to be accurate, Iceland’s external debt – as in the country, represented through the Central Bank – was equal to 57% of the GDP of Iceland in 2003 rising to 104% in 2009, according to World Bank statistics.

Iceland’s banks’ debts were much higher however, reaching nine times the level of Iceland’s GDP in 2007. The result was that, at the end of the second quarter of 2008, Iceland's external debt was 9.553 trillion Icelandic krónur (€50 billion), with over 80% held by the banking sector. This value compares with Iceland's 2007 Gross Domestic Product of 1.293 trillion krónur (€8.5 billion).

So Iceland’s banks were the issue, rather than the country of Iceland.

In fact, Iceland the country is still doing relatively ok it seems, compared to the PIIGS, although it is having to sell off some of its crown jewels to stay afloat.

What intrigued me during the visit were the banks themselves.

If you’re not aware of what happened in the crisis, you can find out over on Wikipedia, from which this brief summary is based:

On 29 September 2008, a plan was announced for the bank Glitnir to be nationalised by the Icelandic government with the purchase of a 75% stake for €600 million. The government stated that it did not intend to hold ownership of the bank for a long period, and that the bank was expected to carry on operating as normal. According to the government, the bank "would have ceased to exist" within a few weeks if there had not been intervention. The nationalization of Glitnir never went through, as it was placed in receivership by the Icelandic Financial Supervisory Authority (FME) before the initial plan of the Icelandic government to purchase a 75% stake had been approved by shareholders.

On 6 October, a number of private interbank credit facilities to Icelandic banks were shut down. Prime Minister Geir Haarde announced a package of new regulatory measures including the power of the FME to take over the running of Icelandic banks without actually nationalising them, and preferential treatment for depositors in the event that a bank had to be liquidated.

The FME placed Landsbanki in receivership early on 7 October. A press release from the FME stated that all of Landsbanki's domestic branches, call centres, ATMs and internet operations will be open for business as usual, and that all "domestic deposits" were fully guaranteed. The same day, the FME placed also Glitnir into receivership.

That afternoon, there was a telephone conversation between Icelandic Finance Minister Árni Mathiesen and UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Alistair Darling. This resulted in Alistair Darling taking steps to freeze the assets of Landsbanki in the UK with the Landsbanki Freezing Order 2008 passed at 10 a.m. on 8 October 2008 and in force ten minutes later. Under the order the UK Treasury froze the assets of Landsbanki, and introduced provisions to prevent the sale or movement of Landsbanki assets within the UK, even if held by the Central Bank of Iceland or the Government of Iceland. The freezing order took advantage of provisions in sections 4 and 14 and Schedule 3 of the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001.

Geir Haarde said at a press conference on the following day that the Icelandic government was outraged that the UK government applied provisions of anti-terrorism legislation in a move they dubbed an "unfriendly act". It is reported that more than £4 billion in Icelandic assets in the UK were frozen with the Financial Services Authority (FSA) delaring the UK subsidiary of Kaupthing Bank in default on its obligations and placed the bank in administration, selling its Internet bank to ING Direct.

On 9 October, Kaupthing was placed into receivership by the FME, following the resignation of the entire board of directors.

As can be seen, these were terrible times and the banks that were in play were no more.

The new banks of Arion Bank, Íslandsbanki and Landsbanki are therefore very different to the banks that disappeared in the storm of the crisis.

Reformed, revitalised and re-energised, the banks are now focused upon the citizens of Iceland and doing a good job for them.

Or so it seems.

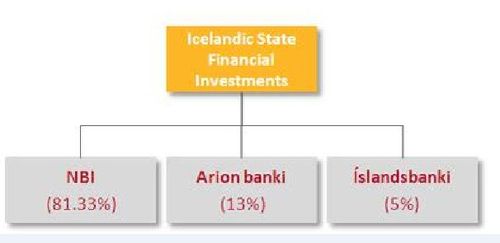

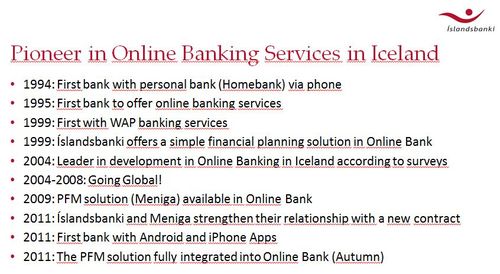

For example, here’s a slide from the Íslandsbanki presentation I received that resonates with the discussions I had with the other banks there:

What this slide shows it that Iceland’s retail banking system has historically been at the very forefront of all technological developments in Europe.

As with most Scandinavian countries, Iceland is virtually cashless – about 96% of all payments transactions are electronic – and everything is online. Over the past few years, 30% of Iceland’s bank branches have shut down, and a further 30% is expected in the next few years.

Mobile is a key focal point today as is Personal Financial Management (PFM) software – Meniga is an innovative Icelandic PFM provider that Íslandsbanki use.

In fact, the most interesting aspect of this slide is that it shows the herd mentality of banks.

The Icelandic banks were all focused upon outdoing each other in the 1990s in the race to deploy innovative technologies for self-service.

They led the world in internet and mobile banking, and created a hotbed of innovation.

Then easy access to securitised lending markets opened up, and they took full advantage of the loans business.

As a result, Icelandic banks gained large-scale operations in UK, Netherlands, Norway and other overseas markets, and their clients did the same with everything from West Ham Football Club to the House of Fraser being prime targets for Icelandic investments.

Not bad for a country about the size of Coventry (UK’s 11th largest city).

Since the crisis hit, and the banks were allowed to be ‘let go’, the country is reforming in a post-crisis world with a new banking order.

One that has returned to its roots of innovation around customer-centricity.

That’s why the rollout of PFM as a platform is a key for the Icelandic banks, and not just Íslandsbanki but also Landsbanki and Arion Bank are rolling out similar platfroms as core.

This may be the reason why: excellent user engagement.

These metrics were shared with me, based upon 18 months of PFM usage amongst Íslandsbanki's customer base:

- Over 25% of online users signed up for stand-alone PFM within 6 months

- Over 75% of new PFM users use PFM again within two weeks

- Over 25% of new PFM users use PFM five times or more in the first month, and spend more than double the time in PFM compared to online bank (the average time onsite is 12 minutes, with 35 pageviews per PFM session)

- More than half of all PFM users are still active a year after signing-up

And their customers love it, partly because it brings in a form of gaming in finance, where you can compare your activity with everyone else's. Here's one of their ads for example:

And, in a recent customer survey, Íslandsbanki found that:

- Over 80% of users are “pleased” or “highly pleased” with PFM

- 9 out of 10 users say they’d recommend PFM to others

- 66% say PFM has helped them see how they can improve financially

- 41% say they have improved financial behavior after starting to use PFM

According to Íslandsbanki:

- Active PFM users have increased the total number of Íslandsbanki accounts (current, savings, credit card) by 19,4% on average after using PFM for 1 year. Other groups show no or slight increase only.

- Active PFM users have increased Íslandsbanki transaction volume by 4,5% on average after using PFM for 1 year. Other groups show no increase.

- Affluent customers are significantly more likely to use and be pleased with PFM than other groups

- There is also evidence of significantly improved retention of PFM users with 71% of users saying that Íslandsbanki‘s PFM offering increases their loyalty

There’s many other stats I could place here, but perhaps the most telling comment is when the bank tells me that PFM is now replacing their online bank.

In other words, PFM is their online bank.

I suggested that PFM is their bank.

They smiled.

This tells me another thing.

If Iceland and Scandinavian banks set the trends for retail banks across Europe, maybe all banks will just be PFMs by the end of the decade.

Now there’s a thought!

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...