Just sat through a day of academic debate about the financial crisis and how much technology was to blame.

We’ve had these blame games many times in the past, usually to try to point a finger at an individual like Greenspan or Brown, so taking the finger to point to an inanimate pile of metal processors was going to prove interesting I thought.

But it wasn’t, as this was run by the London School of Economics who pretty much made the day a disinfected affair with professors emeritus pondering and pontificating.

As one of my friends said: “an academic is someone who looks at something working in practice and wonders what it would be like in theory”, and this was the case here.

However, there were a few brighter spots, including addresses by CIOs from the European Central Bank and Royal Bank of Scotland.

The real point of the whole day was to point to the origins of the crisis – the rich and diverse world of derivatives – and to say that the complexity of quantum analytics that drove us down the spiral of debt was due to the systems handling our formulas in such a way that it made it look like risk was managed … but it wasn’t.

In other words, the computers messed up.

One speaker pointed out that risk was hidden because regulators focused upon individual financial institutions instead of systemic risks across the industry.

Another talked about the origins of the Black Scholes system, and said that “it wasn’t technologists who caused the crisis, but physicists”.

Another mooted the scale of computing, and how complex analytics had moved us into grids, data centres and clouds, that provided unlimited processing and scalability. Hence, what could never have been mapped, simulated or contemplated before could now just be modelled and deployed overnight.

Whatever your view, systems are a contributor to this crisis, but it’s not the systems that caused it but the people who programmed them. So here’s my potted view of how technology exacerbated the crisis and what will happen next …

Back in the 1960s, markets were inefficient and ran on open outcry systems where lots of men stood in pits shouting at each other.

These men were “chaps” and “blokes”, with the chaps being the ones who wore top hats and the blokes bowler hats.

The top hat brigade didn’t like the bowler hat lot – mainly because blokes spoke with common accents shouting out things like “cor blimey guv’nor, catch a load of this stock at five and ten” – and so they found a new-fangled thing called a computer and wondered what they could do with it.

Luckily, two men called Fisher Black and Myron Scholes came up with an exceedingly complex formula which they called the Black-Scholes formula as they were very imaginative.

The formula meant that if you were buying or selling stocks, you could break the buy or sell order into pieces and manage the risk by placing the purchase with other related instruments in a derivative.

Luckily, this formula was perfect for the computer age and allowed the chaps who could afford such technologies to trade bits of equities.

This was no big deal as the processors back then were not very sophisticated – a mainframe would have been the equivalent of your Nokia mobile of five years ago – but it did allow some complex analysis to begin.

In particular, it allowed the age of leverage to start, and introduced new disciplines in market and credit risk.

This bubbling area of derivatives and risk didn’t really take off until the 1990s, when systems had become more and more distributed, powerful and capable. Such systems enabled the chaps to do more hedging and complex investment strategies began. This was further supported by electronic trading, which had also increased in prevalence after the automation of the main markets in New York and London known, over here, as the Big Bang.

Now things were getting a little more efficient, and markets started referring to exotics and “the Greeks”. And risk became more destructive as a result with Nick Leeson destroying Barings Bank; Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) almost blew up the financial world; Frank Quattrone was indicted over the internet boom for misrepresenting IPOs; and Henry Blodget got into trouble for mixing securities research with securities trading.

What was really happening is that the mixture of market greed and gaps in regulations allowed many to create more and more complex risk.

Risk management was evolving and trying to keep up, as were the lawmakers, but creative and innovative masters of the universe were seeing the opportunity to combine processing power and automated trading with arbitrage and exotic instruments to create ever increasing returns at the expense of those who did not have the ability to make these combinations work.

And yes, there were some big deals like LTCM but the markets coped.

That was until David Li’s formula cropped up.

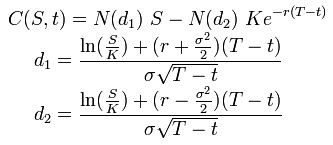

David Li’s formula is the one that almost killed Wall Street, as Wired Magazine so eloquently put it, and it goes like this:

![]()

No big deal.

But it is a big deal as it created a number of false assumptions and operations.

First, it made traders believe credit risk was managed and covered, when it wasn’t.

Second, it ignored real world assets to simulated models, and hence separated two key areas that were mutually inclusive and made them mutually exclusive.

Third, it didn’t incorporate the new forms of market risk we now look towards, namely liquidity risk and systemic risk.

And the real issue that occurred is that the trading systems leveraged the formula to death because, just as this formula was released, electronic trading moved a step forward into algorithmic trading and high frequency trading.

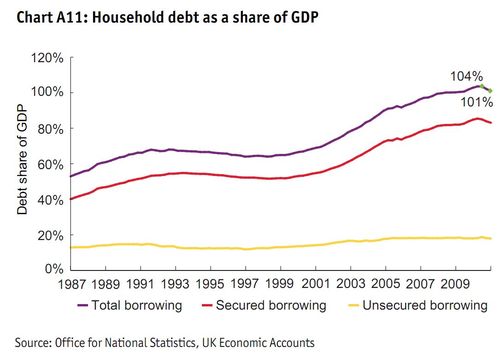

This is why the FSA’s Prudential Risk Report 2011 shows that credit went through the roof over the last forty years.

Similarly, worldwide, OTC Derivatives exploded from a market worth $100 trillion in 2000 to $300 trillion in 2005, growing at thirty percent year on year. It then gathered momentum to grow at forty percent per annum from 2005 through 2008 reaching a peak of almost $700 trillion when the crisis hit.

This debt and credit explosion was a result of the dangerous concoction of leverage, OTC derivatives, unregulated markets, complex analytics and unlimited processing capacity.

This heady mixture had stepped up the financial game into markets that were unmanageable.

From a systems viewpoint, the technology enabled and supported this explosion but was not the cause. The cause is the humans who program the systems.

But the systems capabilities are illustrated well by the fact that, in 2000, the New York markets were processing around 5,000 electronic trade movements per second. This has now risen to levels of over ten million per second.

The financial markets have flared up server processing on an unprecedented scale.

For example, RBS Global Banking & Markets are using over 20,000 server blades for core market processing today, compared to a single processor two decades ago.

And, as the BBC reported last week, those processors are now operating at near the speed of light: “Trades now travel at nearly 90% of the ultimate speed limit set by physics, the speed of light in the cables”.

How fast is that?

Well the speed of light travels at around 299,729,458 metres per second, or near 300,000 kilometres per second, so systems are moving trades around at about 270,000 kilometres a second.

Pretty darned fast if you ask me.

In real life, Professor Doctor Roman Beck of the e-finance laboratory of the Goethe University Frankfurt, says that we’re moving electronic orders around at 5.8 milliseconds between London and Frankfurt. That’s about 52 trips between here and Frankfurt in the time it takes you to blink your eyes (a blink being around 300 milliseconds).

Not bad.

So, we have these completely automated systems processing everything in lightning fast speeds globally with all the opportunities for a bit of a byte of a stock or commodity being built into complex arbitrage systems with unlimited scale and processing power.

Sounds like a recipe for a disaster if you ask me.

And it has been.

But it’s also been a recipe to allow some firms, such as Goldman Sachs, to generate $100 million profit every day that they’re open for business. Consistently.

So where does this leave us?

In a bit of a bind I guess.

We’re not going to get rid of these systems, processors and capabilities are we?

But equally, can we effectively control and regulate them?

I think not.

As the general counsel of Salamon Smith Barney is quoted in Liar’s Poker: “My role is to find the chinks in the regulator’s armour”, and that attitude prevails.

So whilst systems look for chinks, the fragmentation, complexity and geographic spread of systems and regulations allow for arbitrage … and that makes money.

This is why there is no way to demand and force transparency on the markets. For all the calls of the FSA for real-time liquidity reporting, that reporting is meaningless if the Shanghai or San Paolo operation of the financial firm is leveraged to the hilt.

And the idea of a global response to this is also unlikely.

As one speaker said here: “I don’t trust any solutions that claim to be global as most global projects fail”.

Maybe he was involved in the GSTPA or similar ventures.

So the solution: to continue to try to regulate in hindsight and hope that the banks, in foresight, don’t create unsustainable or unmanageable risks.

Or just pray!

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...