I was asked twice yesterday about cloud computing. Firstly by a friend who wanted to know how it related to payments; and then by another mate in the investment world.

The latter was inspired by a new report from IBM and SIFMA that states that cloud computing is ready for prime time:

A survey of over 350 Wall Street Information Technology (IT) professionals has revealed a significant increase in the level of interest in new technologies and computing models, in particular cloud computing, as firms seek to overcome budgetary restrictions and skills shortages.

While there was little change from last year in the perceived impact of all other technologies, the number of respondents predicting that cloud computing would force significant business change more than doubled (from 21% in 2008 to 46% in 2009), making it the top disruptive technology, ahead of even operational risk modeling and mobile technologies, according to the survey's results.

Wall Street and Technology, June 24th 2009

What is cloud computing?

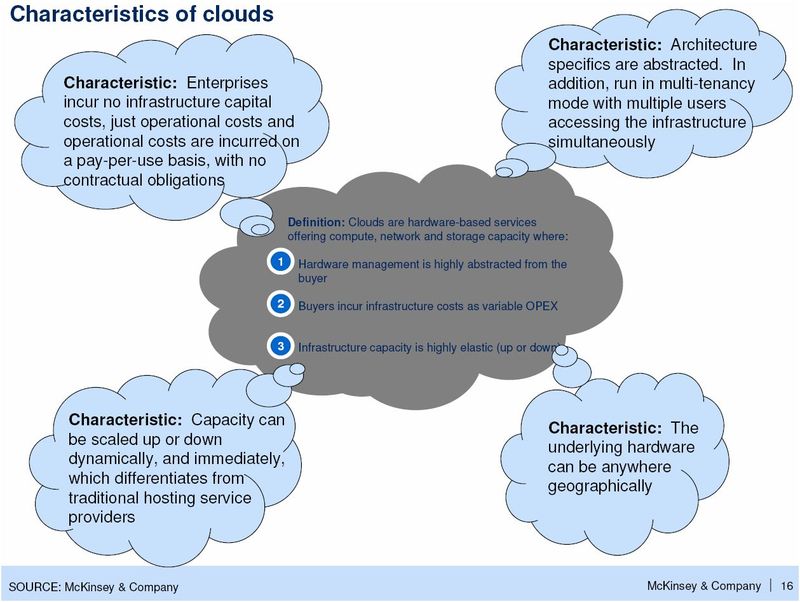

According to McKinsey, they define it as "hardware-based services offering compute, network and storage capacity where: hardware management is highly abstracted from the buyer; buyers incur infrastructure costs as variable OPEX; and infrastructure capacity is highly elastic (up or down)."

Presentation: "Clearing the Air on Cloud Computing" by Will Forest, McKinsey and Company, March 2009

Others call it Software as a Service (SaaS) - see my version of that one - or on-demand computing power.

In a nutshell, it just means you can get extra processing power as you need it, to manage the peaks and troughs of your business needs.

So, why the sudden interest in cloud computing?

Well, it's not that sudden to be honest. It's been a long time coming in fact, and has been discussed often before.

Its time has come however, because the strains and stresses on data centres of City firms means that most are full to bursting.

In investment markets, the firms started to find that the only way to respond to users’ needs – bearing in mind that these users are the most aggressive, macho, alpha males you could possibly meet – was to just sign open cheques to IT firms to sort out their mess.

That might sound extreme, but here’s two examples.

Example 1: Conversion to Euro Processing

It was in the summer of 1998.

A large London-based City bank performs testing of their Euro processing application alongside existing cross-border currency systems on their IBM AS/400 systems.

Systems took anything up to 12 hours to process volume trades in the new multicurrency environment, and were often tied up in batch processes until 10:30 or later in the morning based upon simulated volume throughput.

Problem?

If they went live with such systems, then they were dead meat as no trading could take place until after 11:00 each day, and most spikes in trading volumes occurred in the opening half hour of trading.

Answer?

The bank gave IBM their cheque book and asked them to write in the amount they needed to sort it out … nice business.

Example 2: the Competitor’s Black Box

Move on to the summer of 2005.

A large London-based City bank is processing millions of orders per day, indications of interest, buy-side order routing and other transactions using their latest Order Management System (OMS), deployed in 2003.

It’s all going very nicely, apart from the CIO’s concern that the world is about to fall apart because he’s maxed out in his data centre, can’t deploy any more servers for disaster recovery or business continuity, is using more electricity to run his OMS than Battersea Power Station can generate in a decade, and generally feels their technology capacity is fit to burst.

Then another London-based City bank launches a great new algorithmic trading system and starts gaining liquidity from the buy-side’s order routers through automated order fulfilment.

The head of trading bangs on the CIO’s door and says: “I want one of those”, and points at the latest brochure for sexy algo systems.

The CIO says: “we’ve no space and can’t fit any more tech in here”.

Head of Trading head butts CIO and walks out with an agreement that it will get sorted.

OK, I slightly stretched the last bit, but the reality was that the CIO had to buy a new data farm location in Canary Wharf, fill it with algo tech and ended up spending more in 18 months to compete with the new technologies of the other banks than he’d spent on their total IT architecture over the decade previously.

Both of the above are true stories and illustrate the stresses and strains on City IT.

Now, there are requirements to move towards blade and grid computing, and massively parallel processing systems, as illustrated by Sun’s Blade Farms, or Modular Data Centre as they call it.

These are shipping containers that are dumped in car parks of investment banks and churn away applications in volume. Here’s one:

and inside as you open the doors:

and walk down the corridor of whirring processors:

you open the cupboard and find blade after blade of computing power:

Result?

You can now run thousands of applications requiring gazillions of mips with unlimited capacity, and no longer have to worry about your data centre size and location. Oh yes, it's greener too as it can run on water power and a single feed.

This takes away the issues that my two banks had above in terms of processing speeds, power and resources.

Effectively, any bank could tap into unlimited processing power.

Now, the issue comes up: how much processing power do you need?

And this is where cloud computing comes to the fore.

You see, there’s an old comment: “why would you build a church for Easter Sunday”?

Sure, on Easter Sunday, 1000 parishioners come to the church and pray ... but every other Sunday?

There’s just 10 of the blighters …

... and that’s on a good day.

In a similar way, why would you buy containers of processors if you aren’t going to use them?

And that’s what cloud computing answers.

For example, here's a cloud computing farm:

What these farms offer is vast processing power on an on-demand, as needed, basis.

And this is why it’s being heavily plugged by various firms such as IBM and Sun, sorry, Oracle ...

… and Amazon of all firms.

Yes, Amazon.

In a story I’ve referenced before, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos spoke about how Animoto – a small app for making videos out of personal stuff – went from nowhere to massive in a day thanks to Facebook.

Bezos states that they wouldn’t have been able to do this without Amazon’s Cloud Computing services: “It’s completely impractical in your own data center over the course of three days to scale from 50 servers to 3,500 servers. Don’t try this at home.”

So it’s obvious that if you’re a small bank with minimal data needs except for the odd spike of requirement for an Easter Sunday, then cloud computing makes sense.

Then my mates pipe up: “ah, but cloud computing doesn’t have enough resilience and reliability to be able to manage the volumes, security and needs of FX and other high volume, low latency trading environments.”

Maybe ... maybe not.

After all, the management of these cloud computing farms is the same as internal data farms surely, and if you have Service Level Agreements and contractual arrangements that the provider signs up for, then your rear should be covered.

You may not say that’s good enough for a Goldmans, and it isn’t.

This is because market making firms see technology as their key leverage point and they don’t want to buy in processing power to compete if it detracts from their own processing capabilities.

Going back to example #2 earlier, the very fact these big boys can create these trading platforms is there to decimate the weaker firms that can’t compete.

In addition, Goldmans won’t want their data flowing externally and being open to scrutiny by all, as illustrated by a recent survey where Goldman's placed cloud computing on the bottom of their list of requirements for IT.

However, for your average firm - a firm that doesn’t need to handle and compete with the black box, algo-based, dark pool, big boys - it’s good enough.

Equally, it should be something that large scale secure operators, such as SWIFT, should consider.

SWIFT process billions of transactions per year and offer security, reliability and resilience.

SWIFT could claim this space in the same way as they responded to the challenge five years ago when asked: why do we need SWIFT when we’ve got the internet?

Answer: because the internet is running channels of gambling and pornography, and SWIFTNet offers the additional secure environment to ensure confidence.

Now the question is: why do we need SWIFT when processing, storage and bandwidth is virtually free?

Answer: because you need access to processing, storage and bandwidth that is secure, resilient and reliable, and offers you 100% confidence.

The future of cloud computing in financial services is for operators, such as SWIFT (who are on the case), to offer an Amazon-style cloud computing service for banks to process transactions on spike days, whilst banks manage their own for the rest of the time.

Oh yes, and transactions could be anything from trade executions to payments processing.

Equally, the EBA, Vocalink, Equens, First Data, SunGard, IBM and more could all crowd this space too.

A cloud crowd.

Should be interesting to see what happens.

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...